In October, Prime Minister Robert Abela was hugging people near the parliament, promoting the message “Your mental health matters”.

It’s a message we’ve heard before. A focus on mental health and the introduction of a new hospital were offered in both the 2017 and 2022 ruling Labour Party’s electoral manifestos. Malta has had a mental health strategy in place since 2020.

The government promises ‘transformation’, but is it delivering on key mental health needs?

“None of us can feel secure unless we know that mental health is taken as seriously as physical health by our healthcare systems,” the Prime Minister said in his 2023 speech at the UN.

“To help provide [the needed] reassurance, in Malta we have implemented a comprehensive mental health strategy to build capacity, address causes, and offer continuing support to individuals with mental health needs, and their families,” he added.

His wife, Lydia Abela, also proclaimed, “Going for a mental health check-up should be as normal as going to see your doctor.”

For Health Minister Jo Etienne Abela, the Government’s strategy is based on the protection of mental health in every aspect of society: “Mental health care is a national priority. We believe in one healthcare system, and the first step to breaking the stigma is to combine healthcare that includes mental health as well as physical health.”

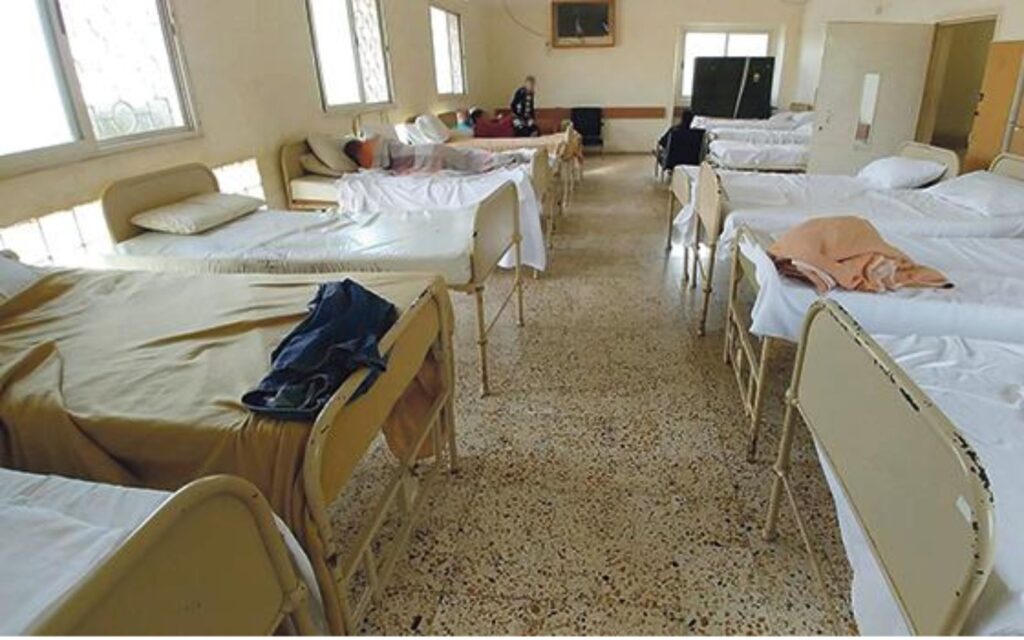

However, when conditions in Mount Carmel hospital, the facility that currently provides inpatient treatment for acute cases (among other services), were criticised, Minister Abela told journalists that “we’re talking about a ward that is giving refuge to people who would otherwise have problems on the streets”, adding that “these are not patients, these are not persons who have been committed to a mental institution”, and are free to leave.

“Many of these people will be suffering from what is known as a dual diagnosis [substance use disorder (addiction) combined with a psychiatric disorder], but their acute phase of the psychiatric disorder is over.”

What is Malta’s state of mental health?

The share of Maltese who reported emotional or psychosocial problems over the past year is 67% – far higher than the EU’s average of 46%. Of those who did, Malta reported a larger share of those who did not seek or find help.

According to Eurobarometer 530, roughly one in eight Maltese respondents saw a psychiatrist for their mental health problems over the past year, and 7% saw a psychotherapist.

A third of Maltese respondents reported they or their family had experienced difficulties accessing mental healthcare – a higher proportion than across the EU. Over half of them complained of long waiting lists and high costs, and a third tried to wait out the problem.

According to the government’s consultation paper, over 15% of adults live with a diagnosed mental disorder – anxiety is the most common among them.

Between 2010 and 2024, Malta recorded 437 suicides (365 male, 72 female). This peaked at 35 in 2021. Comparatively, Malta’s suicide rate is low.

In 2024, there were 26 suicides among residents (22 male, 4 female) and 6 among non-residents (5 male, 1 female), the highest non-resident count on record.

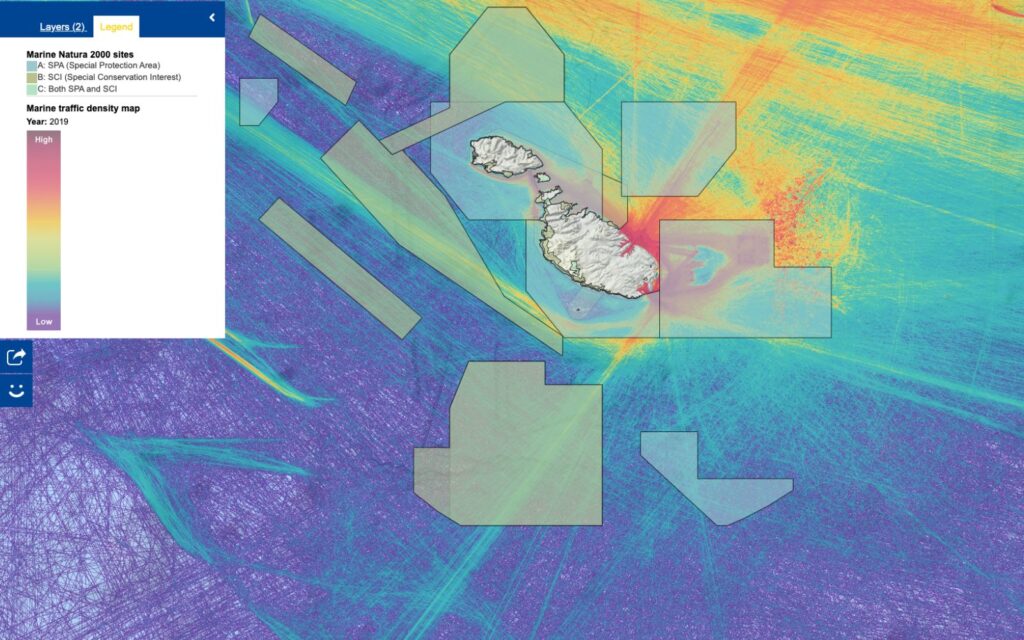

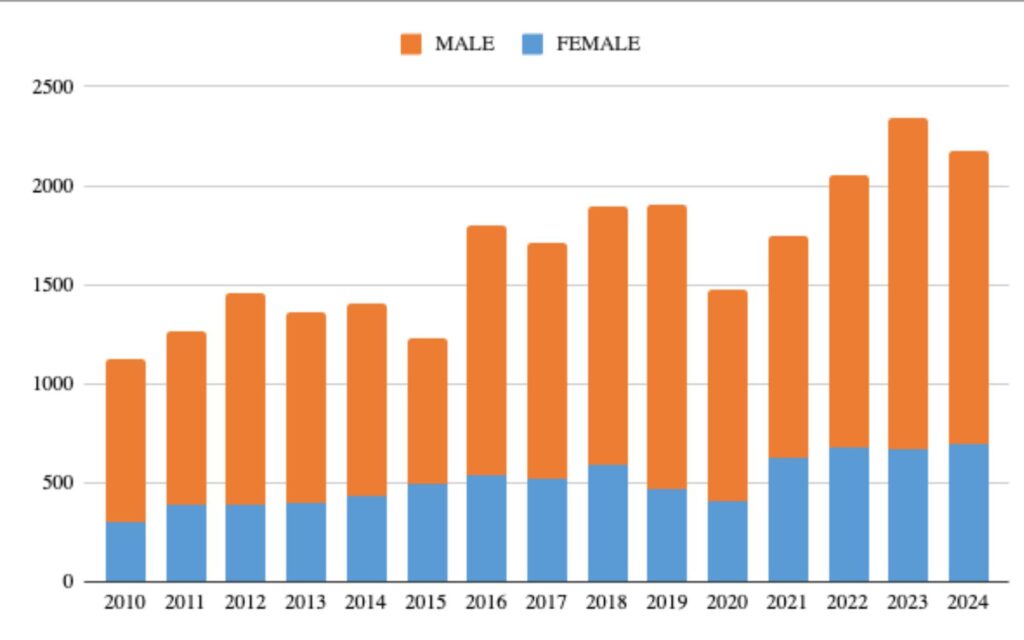

The number of people using services at Mount Carmel has steadily increased over the years, almost doubling from 1,129 in 2010 to 2,171 in 2024.

Meanwhile, the number of persons using Mount Carmel’s inpatient services (both men and women) has increased and exceeded pre-pandemic levels, suggesting continued reliance on hospitalisation.

The number of helpline users, and the number of persons making use of community mental health clinics grew as well.

According to the National Youth Council’s 2018-19 survey, many young people in Malta believed there were insufficient mental-health services, and fewer sought help than the number of those who needed it. Subsequent awareness campaigns have been implemented to increase help-seeking, though publicly reported data confirming an increase in service uptake remain limited.

Key mental health services are provided in the following facilities:

- During the first year of its operation, the Crisis Resolution Home Treatment Team, which can address acute mental health crises without hospitalisation, received 276 cases, and 17 of them had to be hospitalised;

- The Crisis Resolution Home Treatment (CRHT) served 409 patients in its inpatient service in 2024 – the number has been increasing since 2022;

- The number of children aged 10-17 using inpatient services jumped between 2015 and 2016, initially peaked in 2017 before starting to decline before and during the pandemic, and grew again to 120 in 2024;

- Usage of inpatient psychogeriatric services leaped from 42 in 2023 to 169 in 2024;

- As of 2021, there were eight hostels housing 35 mental health patients; data from 2025 shows that 152 people live in mental-health-supported accommodation in Malta, showing NGOs carry a major share of long-term psychiatric housing;

- The use of outpatient services at various clinics soared five times between 2021 and 2022 and grew to 23,429 users in 2024;

- Helpline usage jumped by 29% between 2023 and 2024;

- Patients needing help with eating disorders were predominantly female throughout the years. The number of patients using residential services has been declining, but the use of outpatient services has bounced back post-pandemic, reaching 262 in 2024, the largest number since 2014. A small number of patients used day services.

Noticeably, men make up roughly 83.5% of suicides in the data. This reflects the overrepresentation of men in other areas.

Between 2010 and 2024, 17,358 men utilised services at Mount Carmel Hospital, compared to 7,593 women.

On the other hand, according to an OECD report, depression is more commonly reported to affect women and people on low incomes.

Addictions & Dual Diagnosis:

As noted in the mental health strategy and reiterated by Minister Abela, “Mount Carmel Hospital is partially serving as a place of last resort and final safety net for a significant number of individuals who… do not require hospitalisation in a mental health institution”.

“This situation places further strain on the already stretched resources and can detract attention from seriously ill mental health patients who require hospitalisation.”

Some estimates suggest that dual diagnosis patients (addicts) may constitute between a third and a half of Mount Carmel Hospital’s patients.

For example, the 2023 annual report from the Commissioner for Mental Health found that around 37 patients subject to involuntary admission were found to be homeless.

A study published by the Ministry for Social Policy and Children’s Rights stated that 1,927 individuals were treated for ‘problem drug use’, with the primary drug predominantly being heroin. In 2022, Malta registered four overdose deaths.

Department of Health’s data shows that as of 27 October 2025, 240 patients (176 male, 64 female) were admitted for addiction treatment. Men made up about 73% of all inpatient admissions for addiction treatment.

Community mental health clinics (Paola, Qormi, Floriana, Mtarfa, Mosta, Qawra) handled cases of drug addiction, alcohol addiction, gambling disorder, and dual diagnosis. The Bormla Community Mental Health Clinic separately reported dual diagnoses cases: it handled 45 males and 34 females this year.

Alcohol addiction cases are concentrated among older men (50+), particularly in Qormi and Mtarfa. Drug addiction cases span up to age 77, indicating ongoing treatment needs in older adults.

Figures from Sedqa, Malta’s national agency for substance misuse, show the number of cases worked with, including both inpatient and outpatient interventions, has fluctuated over the past decade, with inpatient cases falling sharply from 287 in 2011 to 119 in 2020, before rising again to 313 in 2024.

Meanwhile, outpatient cases have steadily increased, reaching 1,737 in 2023, and more people started using Richmond Foundation’s neuropsychiatry services.

Crisis Resolution Home Treatment (CRHT) handled nine primary addiction crises in 2025: alcohol (3), cannabis (3), cocaine (2), and polysubstance abuse (1). It also handled 15 secondary addiction-related cases (mainly alcohol and cannabis). Overall, at least 24 CRHT contacts involved addiction. Cases span from 20-year-olds to men in their 70s.

Children & youth:

Malta has among the loneliest teenagers in the EU, according to the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study (2022).

Among 11-year-olds, 11% of boys and 16% of girls in Malta reported feeling lonely most of the time or always, placing them among the higher-ranking EU countries for loneliness in this age group. For 13-year-olds, 13% of boys and 27% of girls reported frequent feelings of loneliness, again ranking Malta above the EU average. Among 15-year-olds, 19% of boys and 30% of girls reported feeling lonely, higher than in other small countries such as Cyprus and Slovenia.

Although the situation for 15-year-olds is somewhat less severe compared with some other EU countries, the proportion of adolescents reporting loneliness remains concerning. Data on 15-year-olds’ mental health well-being indicate that Malta also ranks relatively low within the EU.

UNICEF data based on estimates from the IHME, Global Burden of Disease Study, 2019 shows that more than one in six of Malta’s adolescents (aged 10-19) had a mental disorder and that over 7,000 children and teenagers were in need of care.

In response, specific services target young people:

- The Child and Young People’s Services at St. Luke’s Hospital offers multidisciplinary services available by referral from a general practitioner;

- The Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Emergency Services offers emergency services for young people aged 3 to 18 years;

- The Crisis Intervention and Home Treatment team offers an intensive intervention to young people recently discharged or require extra support;

- The Generic child and adolescent mental health clinics offer an assessment and intervention to all young people aged 3-18 years;

- Family Focused Clinic provides a service to children and young people whose mental health is being negatively impacted by family dynamics;

- The Anger Management Group Therapy trains young people to control their anger outbursts better;

- The Young People’s Unit at Mount Carmel Hospital separates young patients between the ages of 12 and 18.

Malta’s two public education institutions, the University of Malta and MCAST, run their own mental health services. According to official data, 33 MCAST students are currently in active follow-up with the Paola mental health clinic (19 males, 14 females). The University of Malta’s Health and Wellness Centre recorded 4,165 student consultations since 2020, with 44 students seen in 2024.

Non-Maltese residents:

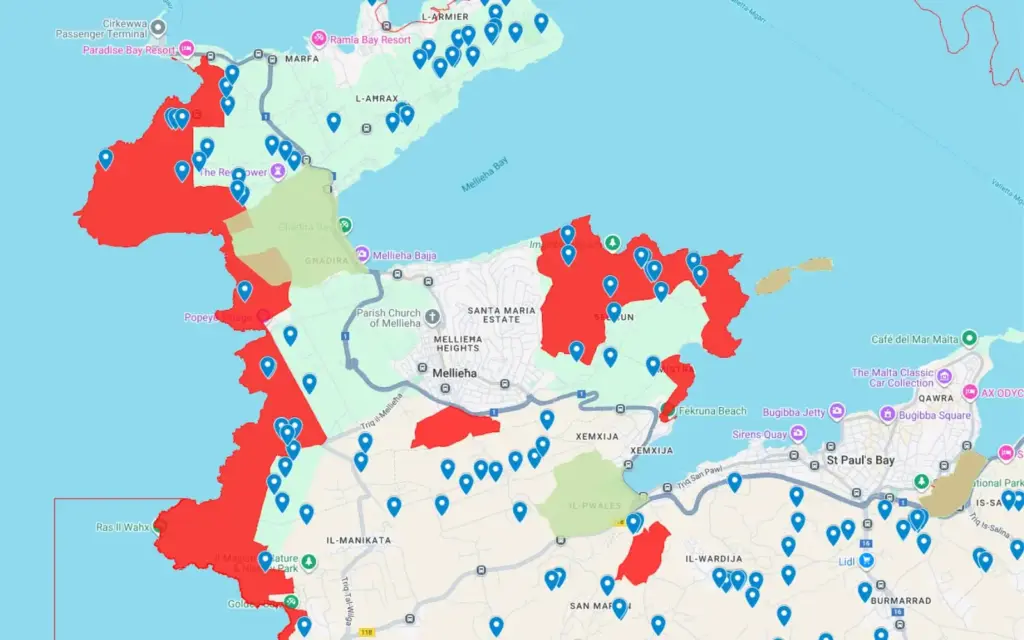

A Mental Health Strategy for Malta 2020-2030 acknowledged that “The risk of admission to the psychiatric in-patient facility, Mount Carmel Hospital, for non-Maltese persons is 2.2 times that of the general population, whilst for persons from low and middle-income countries residing in Malta, the admission rate is 5-fold that of the general population”.

The Commissioner for Mental Health’s 2023 report states that among patients subject to involuntary admission, almost 30% were non-Maltese (188 patients), and over half of them came from non-European countries.

How does Malta invest in mental health?

In the mental health strategy, the government acknowledged that “the focus of the mental health sector regretfully remains somewhat hospital-centric” while community care services were “generally understaffed”.

A 2022 study stated that substantial reform in mental health services only started during the pandemic, despite attempts starting in the early 1990s. “Past attempts at reforming this sector were stifled due to insufficient and unsustained political commitment, leaving it direly under-resourced,” the authors wrote.

The budget for mental health services has been gradually growing: from more than €42 million in 2019 to €71 million in 2025. However, the demand for outpatient services skyrocketed between 2021 and 2022, with an increasing overall trend.

Mount Carmel Hospital is the institution that provides inpatient mental health services, residential treatment centres, community mental health centres, and outpatient clinics.

Budget documents over the years show that investment in the Mount Carmel hospital skyrocketed in 2020, then declined, and picked up again in 2023, when “acute psychiatric hospital” became a separate expense category. Crisis intervention’s budget has been stable since 2019, except for a temporary dip in 2022.

The Commissioner for Mental Health noted that, as of 2023, the lowest-quality treatment wards suffered from “poor facility upkeep, poor ventilation, lack of designated smoking areas, lack of activities and privacy in the bathroom and toilet areas, as well as in the sleeping areas.”

The Commissioner went on to call for “increased allocation of funds in the next national budget to better assist patients with a dual psychiatric disorder and substance misuse.”

However, the only time substance abuse/ misuse is mentioned in the budget 2026 document is the allocation of funds for the Advisory Group/Committee on Substance Abuse. It will receive less money than in 2025.

The 2022 study showed that the sector suffers from a shortage of nurses and social workers – key staff essential for the desired transformation.

The study’s authors noted that the government was not leading the way in the reform – it reacted to pressure from the mental health commissioner, the National Audit Office, local media, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and professionals.

Politicians’ recent claims on mental health policy concerned promises of a ‘transformation’ in service provision with an inclusive, patient-centred approach. Robert Abela spoke of a mental health strategy that has already been implemented.

According to researchers, “The lack of sustained political commitment and investment greatly undermined mental health reform in the past, while strong advocacy from stakeholders was key to bring mental health back on the political agenda”.

Since then, the government has promised to integrate physical and mental health, build capacity, and make the system more accessible. A range of services for children and young people is available to address the pressing needs of this population.

Meanwhile, data shows that Malta’s state of mental health is rather alarming: a significant share of individuals experiencing problems do not seek or find help, and available resources are not addressing key gaps: social isolation among adolescents, exclusion of migrants, and complex needs of substance addicts.

Allocations for mental health services have been increasing over the years, and funding for Mount Carmel Hospital recovered in 2024 after a decrease. However, crisis intervention, which experiences a high demand, has not seen an increase in its budget.

Despite financial improvements, there is no evidence of earmarked budgets to address the most pressing needs, namely, training and recruiting more nurses and social workers to address the shortages of this essential personnel. Some efforts to recruit cultural mediators are included in the integration strategy.

Thus, although a reform has been taking place and resources have increased, the impacts fall short of a fully fledged transformation. The claim is only somewhat true.

This project is supported by the European Media and Information Fund. The sole responsibility for any content supported by the European Media and Information Fund lies with the authors and it may not necessarily reflect the positions of the EMIF and the Fund Partners, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute.