- Budget 2026 allocates €160 million in tax cuts and grants to reverse Malta’s declining birth rate, as the government’s response to concerns over the native population’s future and demographic decline.

- Projections by the Central Bank show the Maltese and Gozitan population could fall from 405,000 in 2024 to around 275,000 by 2075, even under favourable scenarios.

- According to the Central Bank report, Malta’s native population reached 405,075 people, increasing by almost 6% since 2000, and 2.3% from 2010.

- Fertility rates fall: Malta’s total fertility rate stands at 1.06 births per woman (2023), the lowest in the EU. However, among Maltese women, it is higher at 1.16, towards the top end of EU levels.

- The term “native” refers to a Maltese National, which remains undefined in Maltese law and policy. A citizen is anyone with a Maltese parent and/or acquiring it through nationalisation or formerly investment, though Central Bank data excludes them.

- A study found that the majority of Maltese genes could be attributed to West Eurasian roots.

- However, studies also show that Maltese relate identity more with social characteristics rather than birthplace.

- Malta’s population has grown by 135,000 since 2014, this has been driven by migration, with 1 in 6residents now foreign-born. There is no birthright citizenship in Malta if both parents are foreign.

- International evidence shows mixed results:

- Hungary’s fertility rose modestly after family tax cuts.

- France’s success stems largely from strong childcare and parental support systems.

- South Korea’s tax incentives have failed to reverse record-low fertility due to rigid work and gender norms.

- Verdict: Fertility decline is real, yet tax cuts alone are unlikely to reverse it without broader social and structural reforms.

Budget 2026 is here. Malta’s Prime Minister Robert Abela described it as “the best in history”. At its core lies a fiscal plan to reverse Malta’s declining birth rate. Tax cuts and grants for parents, worth €160 million per year, headlined Finance Minister Clyde Caruana’s budget speech.

In 2025, Caruana and others, including Archbishop Charles Scicluna, warned about the decline in fertility and its implications for Malta’s native population.

The debate unfolds against the backdrop of rapid population growth, fuelled mainly by migration. But what does it truly mean to be “native”? What do the figures reveal about Malta’s wider demographic challenges? And will the new proposals address the issue?

In a pre-budget meeting with social partners, Finance Minister Clyde Caruana reportedly said that Malta’s fertility rate is “the greatest challenge of our time”.

“Where will our population be in 50 years’ time?” Caruana reportedly asked. “Will we be at a point of no return?”

In an episode of Karl Bonaci’s podcast, he went one step further:

“If we do nothing and everything stays as it is […] Maltese and Gozitans, within 50 years […] will drop from 400,000 to 240,000. […]It means that out of those 240,000, 40%, almost 100,000 people, will be over 65 years old.”

“When I was born in 1985, there were 6,000 Maltese boys and girls born that year […]. Today, only half that number are being born, around 3,000 Maltese in total.

“We talk about wanting to preserve our culture, we talk about wanting to preserve our language, but at the same time, we are forgetting that we ourselves may be digging our own grave, and tomorrow, maybe the day after, these people could vanish into nothing, because there won’t be enough of them left living on this land.”.

The Archbishop, Charles Sciclina, claimed Malta risks the “extinction of our ethnicity”.

“What our enemies did not manage to do, we are doing with our own hands,” Scicluna said.

The ‘Native’ Population Numbers

Malta’s population has increased by more than 135,000 since 2014, reaching 574,250 as of 2024. Today, one in six residents is a foreign national. A report published in 2023 by the Ministry of Finance projects that the total population will exceed 810,000 by 2070.

A Central Bank policy note from May 2025 explicitly explores Malta’s native population and its projections and implications on the local labour supply.

According to the Central Bank report, Malta’s native population reached 405,075 people, increasing by almost 6% since 2000, and 2.3% from 2010. It is projected to decline to about 347,000 in 2050 and around 275,000 persons in 2075.

The Central Bank report’s projections show that by 2030, 73.4% of the native Maltese population will be of working age. According to the Central Bank’s models, this is projected to decrease to 70.8% by 2050 and to remain at 63.6% by 2075.

It outlines three scenarios:

Scenario 1: Mortality and fertility rates will change in line with Eurostat’s assumptions in the EUROPOP demographic projections, and migration continues at the current pace.

Scenario 2: Fertility remains the same, the native population remains under the same assumptions as in the baseline but keeps the fertility rate of Maltese women unchanged at the current level.

Scenario 3: Fertility remains unchanged and migration halts.

Overall, the Central Bank’s projections indicate that low fertility rates remain the dominant factor in the forecasted decline, regardless of the scenario, whether that involves Maltese inward migration, replicating EU trends, or maintaining current trends.

“Without a significant change in fertility trends, the long-term demographic outlook suggests stronger population ageing and potential labour force challenges,” the policy note reads.

Malta’s total fertility rate has declined sharply over the past 50 years. In 1977, the total fertility rate was 2.14 births per woman. In 2023, it stood at 1.06, below the EU average of 1.38.

However, the fertility rate among Maltese women specifically stood at 1.16, which implies the actual rate is not “entirely reflective of the trend within the native population”.

What is a “native”?

In the Central Bank policy note, ‘native’ refers to a Maltese national, which is not explicitly defined in any legislation in Malta, not even in the Citizenship Act.

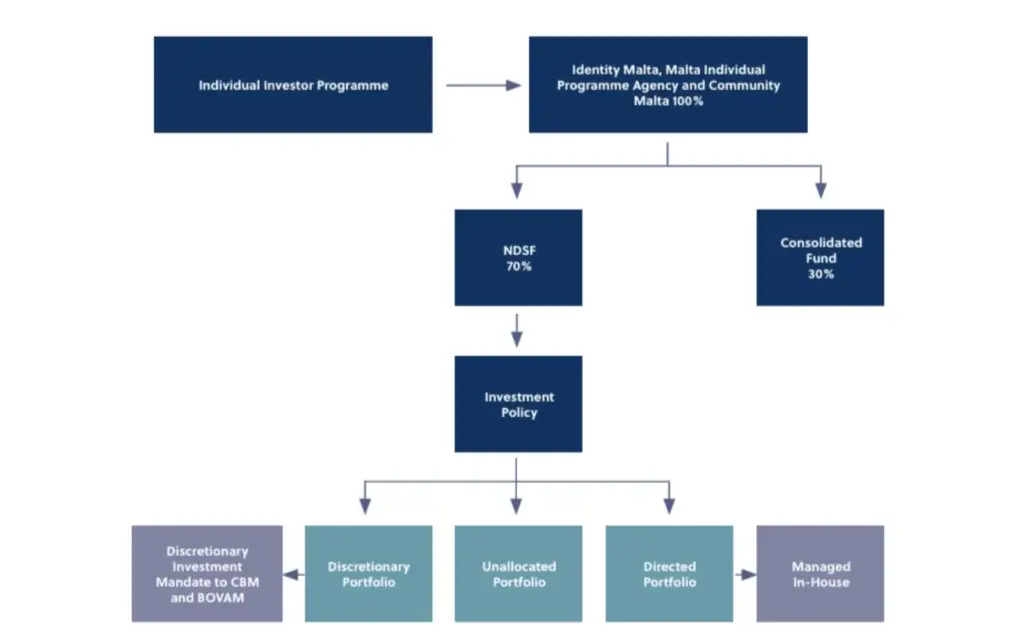

The Central Bank policy removes all persons who may have acquired citizenship, either by naturalisation or formerly investment and now exceptional merit.

Unrestricted birthright citizenship ended in 1989. Since then, children born in or outside the country have only been granted citizenship if at least one of their parents is a Maltese citizen.

Foreigners with no Maltese ancestry can become citizens through naturalisation, which takes at least seven years, or through marriage.

A person “who renders exceptional services or who makes an exceptional contribution, including through job creation,” or “whose naturalisation is of exceptional interest” can also become a citizen.

A study published in the Annals of Human Genetics in 2006, which involved Prof Alex Felice, found that most contemporary Maltese males trace their ancestry to Sicily and Southern Italy based on Y-chromosome analysis. Subsequent mitochondrial DNA studies, including results from the ongoing Maltese Genome Project, indicate that females show a similar ancestry pattern.

In 2018, a separate study found that the majority of Maltese genes could be attributed to West Eurasian roots, with some presence of African lineages.

However, a 2013 Malta Today survey found that just 8.3% of respondents saw citizenship, and 7.7% saw birthplace, as key to being Maltese. Most instead pointed to language (68.2%), culture (22%), food (15.7%) and religion (14.3%) as stronger markers of identity.

Prof. Gordon Sammut has explored the social characteristics behind Maltese identity. The study, which explored two surveys from 2011 to 2021, delves into how identity is shaped through comparison and shared meaning within groups.

Our surnames, also, represent a “huge melting pot”, as one study by Mario Cassar puts it. Cassar distinguishes between surnames of Romance origin, such as Italian, French, or Spanish, and more recent European surnames, noting that “the spate of British, Irish, German, and other European family names accumulated through relatively recent ethnic intermarriages..

Marriage records from the Renaissance period show that around a third of grooms in certain localities were foreigners. There are a number of Indian surnames present in more recent centuries, like Melwani, Balani, Mohnani.

What are the proposals?

Budget 2026 outlined several proposals targeting parents. These included:

- New income tax bands for parents. This will eventually extend to parents with two or more children paying 0% income tax up to €37,000 by 2028, and to parents with one child paying 0% income tax up to €22,500. For single parents, that figure will be at 30,000 and 18,000 respectively.

- Grants for parents having their first child, including by adoption. They will now be €1,000; those on their second will get €1,500; and parents will receive €2,000 for every child beyond that.

- A refund of €12,000, up from €10,000, for parents hoping to adopt overseas. If adopted locally, the grant will double from €1,000 to €2,000.

- Increase of Children’s allowance to €250 per child. For families earning under €23,000, there can be an additional €167 per child, making the total increase higher.

The government has also noted the fertility issue in the Social Plan for Families (2025-2030). In it, it calls for “enhancing” the fertility rate through “family-friendly workplace policies”, “affordable housing and financial stability”, “education and awareness programmes” and “data collection and research”.

The populous town of St Paul’s Bay only has two free childcare centres, and so does Sliema, where demand is also high.

As of early 2024, after-school centres in Sliema and St Paul’s Bay had waiting lists of 25 and 28 children, respectively. According to the 2024 financial estimates, the government reduced funding for after-school clubs by almost half, from €9 million to an estimated €4.8 million, between 2023 and 2024.

What has happened elsewhere?

The impact of tax incentives on fertility remains uncertain.

Hungary has introduced income tax deductions and other family-focused measures. This has helped lift fertility from the low 1.23 in 2011 to around 1.55 in 2023.

A study by the HETFA research institute suggests these incentives account for part of the increase, but other social and economic factors also played a role, including employment, nursery school availability, and flexible work possibilities.

In France, where fertility has stayed among the highest in Europe, it has a wide range of social and population policies which experts point to as the “most obvious explanation”, namely an extensive childcare system, including public crèches and écoles maternelles, that offer affordable, high-quality care from age two or three:

In South Korea, which has the worst fertility rate in the world, tax cuts have made little difference. Korea has made significant strides in family policies; however, according to the OECD, “they still fail to fully meet the diverse needs of working parents”.

“Moreover, rigid gender norms and entrenched labour market practices further exacerbate these challenges, especially for women, who are often forced to choose between pursuing a career and raising a family,” it reads.

Claims that Malta’s native population is on the verge of collapse are alarmist and are based on projection models that assume little change to fertility & exclude all children born to a foreign mother. However, demographic concerns are very much a reality.

Data does show a decrease in native populations over the last two decades. However, it also ignores several factors, including whether foreign nationals residing in Malta will, in the future, marry Maltese nationals and contribute to Malta’s biological mix.

There is also very little definition by the government or the constitution as to what precisely a native person is. Experts have pointed to biological determinants that link us to the broader Mediterranean mix, rather than to something expressly ‘Maltese’.

Government proposals to address the issue in the budget are a notable first step. While studies suggest that tax cuts and similar grants could slightly improve fertility, more needs to be done to address other conditions, such as the quality and accessibility of childcare, as well as other social policies.

The claim that Malta’s population is at risk of decline and that tax cuts can save it is only partially true.

This project is supported by the European Media and Information Fund. The sole responsibility for any content supported by the European Media and Information Fund lies with the authors and it may not necessarily reflect the positions of the EMIF and the Fund Partners, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute.