By Daiva Repečkaitė

- Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), the EU’s flagship funding stream for farms, mainly benefits road building, wineries, the poultry sector and Project Green in Malta;

- Project Green was the largest single beneficiary of the €166 million fund, receiving €15.8 million, with no clear links to farming.

- Over €1.2 million went to Infrastructure Malta road-building projects.

- The authority claims it benefited over 308,508 persons from the ‘rural population’, which is more than half of Malta’s population, and dwarfs the number of registered farmers.

- Wine producers benefited from CAP’s basic income and environmental measures.

- Montekristo, which ran unsanctioned operations until 2025, also benefited.

- Farmers’ representatives have repeatedly voiced their needs: help acquiring land, reduced bureaucracy, and market access. “I had to drive around the island on the day of the deadline to find the right office,” farmer Cane Vella said about bureaucracy.

- At an average of over €201,000 per hectare, the purchase price of arable land in Malta is by far the highest in the EU, while rental rates are far below the EU average at €91 per hectare.

- CAP distribution is questioned not only in Malta; reporting from Italy shows that the selection process disadvantages small farmers who market products locally, even though small farms were historically dominant in Italy.

This investigation is part of Senza Segnale, a collaborative project. Together with Facta, Amphora Media reviewed who benefits the most from CAP and who is left out.

In Malta, most EU farm subsidies do not reach farmers. Data shows a large proportion went to roads and infrastructure investments. Wineries, the poultry sector and even Project Green scored big.

An analysis by Amphora Media of data published by fondi.eu and the Agriculture and Rural Payments Agency (ARPA) indicates that, since 2023, the majority of funds under the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) have been captured by government bodies, while individual farmers have received a much smaller share.

“There is an office in Ta’ Qali with fifty farmers sitting half a day waiting,” farmer Cane Vella says of applying for a young farmer subsidy. “When you get inside, it’s very rushed.”

When the European Commission approved Malta’s CAP plan in 2022, Agriculture Minister Anton Refalo said that European Funds “will continue to assist all workers in this field.”

“The EU scheme is straightforward, but land registration is not,” Vella says. “There is no handbook.” Farmers’ representatives echoed the lack of coordination and strategic vision among government entities.

How does the EU fund Maltese farming?

The CAP is one of the 19 EU funding streams implemented by the government. It is financed through the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD).

In Malta, the Funds and Programmes Division within the Ministry for the European Funds oversees CAP funds as the managing authority. Applications and payments are processed by the ARPA.

CAP goals include supporting farmers to help them “make a reasonable living”, sustainable management of natural resources, and keeping the rural economy “alive” by promoting jobs in farming, agri-food industries and associated sectors.

Between 2023 and 2027, Malta will distribute a total of €166 million (EU funds and Maltese co-financing).

Discover the key priorities for Malta under CAP cap:

| Type of investment | Funding allocated (€, rounded) |

| fostering, slurry management and wastewater networks | 31 million |

| investments in new technologies, digitalisation, smart and improved irrigation systems | 21.3 million |

| basic income support rates for farmers | 15.6 million |

| coupled income support (per animal or hectare of land) | 15 million |

| support for more ecological agricultural methods | 10 million |

| schemes for young farmers (under 41) | 8 million |

| knowledge, exchanges, and training for farmers | 4.3 million |

| schemes for small farmers | 2.4 million |

| incentives for organic farming practices | 2.3 million |

| incentives for animal welfare | 1 million |

| measures for apiculture (beekeeping) practices | 141,000 |

Pillar 1: direct payments to farmers

Pillar 1 consists primarily of a direct income supplement for farmers to ensure their income stability and to recognise other benefits, including their role in caring for the countryside. This is entirely EU-funded.

Across the EU, nearly two-thirds of CAP funds are paid out this way. Between 2023 and 2027, nearly €43 million has been allocated to these direct payments in Malta.

Basic income support is evenly distributed, with the top 10 recipients sharing around 2% of the pot. The largest beneficiaries, Meridiana and Marsovin wineries, received over €26,500 between them.

Pillar 2: rural development and investments

In Malta, the first pillar is dwarfed by Pillar 2, which funds rural development measures including infrastructure, training schemes, and other investments.

Here, unlike Pillar 1, national governments co-finance and select projects under a national programme.

In Malta, EU funding for Pillar 2 is set at nearly €100 million for the funding period (around €76 million in EU funds and more than €41 million in national contribution).

Malta’s Government is the Major Winner

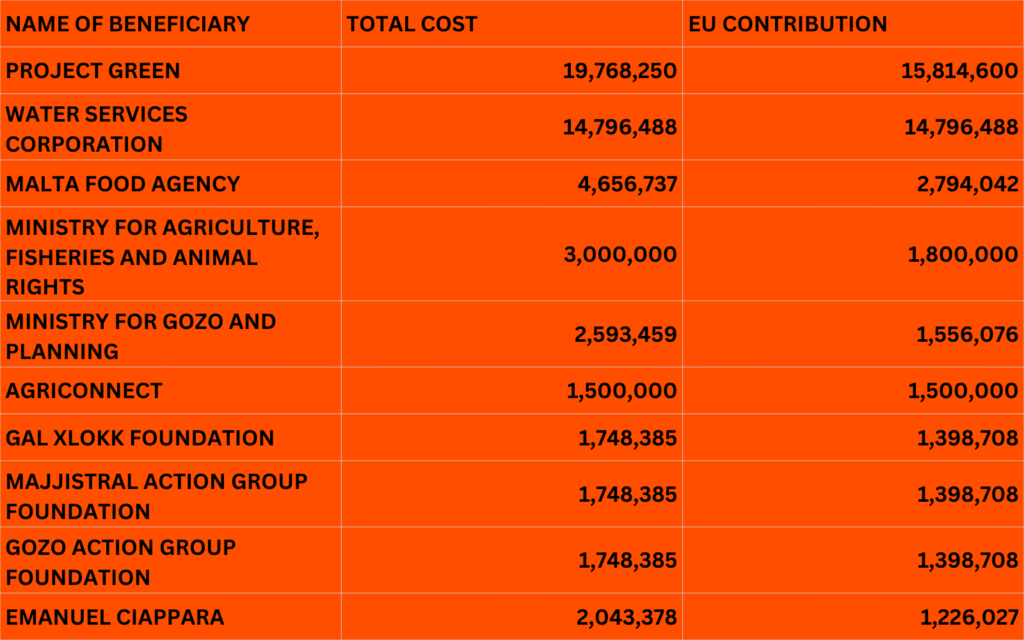

The published list of Pillar 2-funded projects shows that government bodies were the substantial beneficiaries of CAP funds:

- Around €40 million in EU funding, or 65% of allocated Pillar 2 funds, went to the central government.

- If entities like the Public Abattoir and the University of Malta, a public university, are included, the public sector’s share rises to nearly €42 million in EU funding, or 68% of Pillar 2.

- In contrast, farmers were collectively allocated almost €14 million in EU funds from this (rural development) pot.

ARPA’s data shows that in 2023-2024, public sector entities accounted for the largest share of total funds disbursed.

The Ministry for Gozo and Planning received funding from three measures, the largest payment being for Investments in physical assets – over €986,000.

‘Local’ Funds for Project Green

The largest share of EU rural development funds went to support region-based local action groups, which together were allocated over €20 million to projects worth around €25 million.

Project Green, a centralised government agency, was the single largest CAP beneficiary, receiving €15.8 million, more than any individual local action group, which received some €1.4 million each, despite guidelines stating it is intended for non-profit local action groups.

Project Green’s CAP funds have been used to clean up Wied Għajn Riħana, remove illegally dumped waste, and support ‘afforestation’.

Project Green and ARPA did not respond to questions.

Water Upgrades: Useful, But Not for All

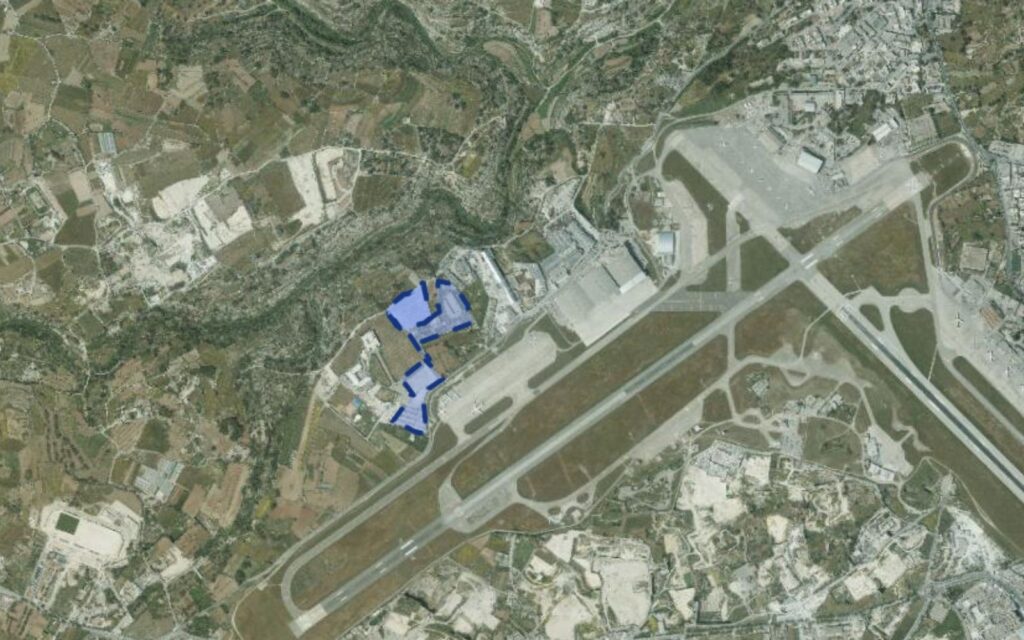

The second-largest chunk of EU funds, €14.8 million, went to Water Services Corporation (WSC) for “Upgrading The Production Capacity of Reclaimed Water in Gozo and Malta North”.

In 2024, WSC distributed 1.5 million cubic meters of New Water: 0.35 million in Gozo, 0.77 million in Mellieha, and 0.37 million in Marsaskala. WSC reports that more than 1,800 registered users of the water supply

“The issue is that it is very unreliable. Sometimes there’s water, sometimes there’s no water,” Malcolm Borg of Għaqda Bdiewa Attivi, a farmers’ organisation, told Amphora Media.

“Not all farmers get this new water,” he continued. “This is causing a bit of unfair competition.”

In an interview with TVM, a farmer who lacked access to recycled water said he spent at least €4,000 per year irrigating his land.

A farm map by Friends of the Earth Malta shows a high number of farms in Rabat (Malta), Attard, Zebbug (Malta), and other areas that are not covered by New Water dispensers.

The Western district, for example, had the largest number of agricultural holdings (as of 2020), yet it is not served by recycled water.

In a government consultation, one part-time farmer wrote that a recycled water connection he applied for “never worked” and remained out of service for nearly a year.

Road building takes over a million euros in CAP

Published data show that Infrastructure Malta was allocated over €1.2 million to “improve accessibility to farmland”.

For 2023, ARPA reported that 308,508 persons benefited from this as part of the “rural population”. This is more than half of Malta’s population, and far surpasses the number of registered farmers.

“Farmers sometimes complain that their road is not [great], but it is very low on the priority list of farmers,” Malcom Borg told Amphora Media.

“Agricultural fields are being used for recreational purposes – those people want good vehicle access to rural areas,” he claimed.

“Improvement in rural roads was an investment that was long overdue. But there are other pressing matters that need more attention and are not necessarily solved through funding, but through more organised public administration,” comments Jeanette Borg, who has founded and runs the Malta Youth in Agriculture Foundation for young farmers.

The organisation she leads has been active in policy dialogue.

In October, it brought together farmers, students, and tech industry representatives to develop ideas for tackling land access and water resilience, among other issues.

One of the key discussions centred around the question “Why are farmers often forced to choose short-term survival over long-term investments such as training and marketing?”

“We’re an arid country. It’s getting worse, so I would prioritise building reservoirs and research about pest control,” Jeanette Borg said. “Farmers face many stumbling blocks by the Planning Authority in building reservoirs, and we do not even have a national lab that can test for pesticide residues.”

Borg also co-authored a study on young farmers. It showed that the main challenges they identified were resources, market issues, and a lack of assistance from authorities.

She is adamant that Malta must fix its food production system before trying to entice young people to become farmers.

The Malta Food Agency and the Ministry for Gozo and Planning emerged among other top CAP Pillar 2 beneficiaries, as did AgriConnect, an advisory service for farmers.

Emanuel Ciappara, a chicken-farm operator, was the only farmer to make the list of top 10 beneficiaries of Pillar 2 schemes.

“My clients are already benefitting from the funding received through the latest machinery and innovations in the poultry sector and are currently enlarging the production capacity to meet the demand for local poultry that is a staple for a healthy diet,” a lawyer representing Ciappara said in response to Amphora’s questions about the grant awarded.

CAP funding is at odds with farmers’ needs

Farmers’ representatives say the most urgently needed interventions are elsewhere. Unaffordable land, overexploited aquifers, competition and complicated bureaucracy are acute pressures.

Unaffordable Land:

Eurostat shows that, at over €201,000 per hectare on average, the purchase price of arable land in Malta is by far the highest in the EU, although renting land is well below the EU average and cheaper than in most countries, at €91 per hectare.

“In Malta, one of the smallest countries in the world, land comes at a premium, and access to land is very limited. So if you have a new farmer, it’s almost impossible to enter the sector because they don’t have access to land and water,” Malcolm Borg says.

Bureaucracy:

“I’m afraid that the applications are very complicated, and most farmers would not have the knowledge of how to fill these in,” Jeanette Borg told Amphora Media.

“There are two major departments or entities that are stumbling blocks: the Lands Authority and Planning Authority.”

Approximately half of the total declared land and of used agrarian land is rented from the government and, according to Malcolm Borg, “is managed disastrously”.

Jeanette Borg agrees. “The Lands [Authority] is not organised, and whenever farmers go to change the tenureship, it’s a nightmare,” she told Amphora.

“I had to drive around the island on the day of the deadline to find the right office,” farmer Cane Vella remembers about his experience applying for a subsidy.

Lands Authority and the Ministry for European Funds and the Implementation of the Electoral Programme did not reply to Amphora’s questions.

Local farmers face significant competition from foreign exports:

Malta relies heavily on agri-food imports from other EU countries, exporting very little. Its agri-food trade with non-EU countries, including the UK, is more balanced.

Malta buys at least €155.6 million worth of agricultural produce from Italy, its top importer of animal and vegetable products, accounting for nearly a quarter of all imports.

In 2024, Malta imported from Italy:

€43.77 million worth of dairy, egg and honey products,

€31.3 million worth of meat,

€25.9 million worth of fruit,

€20 million worth of vegetable, nut, mushroom etc preparations,

€17.1 million worth of vegetables,

€8.3 million worth of oils,

€3.7 million worth of seeds,

€3.1 million worth of grains,

€2.2 million worth of cereals.

However, research by Facta, our partners in this investigation, shows that small Italian farms struggle equally with access to land and credit, as the CAP system favours economies of scale.

Small and local Italian farms also disproportionately suffer from ‘informatisation’ of agriculture – having to submit indicators to relevant authorities for monitoring, Italian wine researcher Alessandra Biondi Bartolini told Facta.

“Those operating in disadvantaged or remote areas often lack a reliable internet connection, which becomes a major obstacle: these are people who have to get off the tractor and go into an office, and time is scarce,” she explained. Facta also notes that farmers cannot apply for subsidies directly – they must use consultants, who take a cut.

How are the subsidies reaching farmers?

Large farm projects (worth over €30,000) accounted for the third-largest share of EU CAP funds in Malta, benefiting 104 farmers, with average projects below €120,000.

A €1.95 million scheme supported 393 farmers with small on-farm investments, averaging €4,961 each, for equipment and upgrades.

To apply for support, farmers must show they can cover the remaining 40% of costs, either with their own funds or a bank loan.

Ensuring that expenses are eligible is a challenge, says Cane Vella, as farm expenses are diverse and sometimes unexpected.

“Engine failures. Implements breaking. Pump failures. Rats eating pipes. Hailstorm destroying crops. These are just a few common occurrences,” he lists these unexpected costs.

“Farmers say: Don’t make orders before the subsidy is in your bank account,” he says.

Who benefits most: private operators and CAP funding

The list of private individuals benefiting from subsidies is published without identifiers, making their areas of activity difficult to verify.

Among the largest 2023-2024 beneficiaries that applied as legal persons were:

When asked to explain why an event caterer and a communications company received agricultural subsidies, ARPA promised to respond. Weeks later, its reply was still not ready.

Animal products get a strong focus in CAP

The choice of which sectors CAP supports has received international criticism.

“The CAP has always favoured intensive agricultural species like cereals, corn, etc, along with livestock. It has never been a tool in favour of maintaining small multifunctional farms, nor of the agro-ecological transition,” says Italian agronomist Riccardo Bocci.

In terms of production value at basic prices, vegetables and horticulture (growing garden plants) in Malta account for by far the highest share, a third (33%) of all output value. They are followed by milk (20%), eggs (12%) and poultry (10%).

Jeanette Borg and colleagues’ study found a strong interest in fruit and vegetable farming among young farmers: a third of those surveyed grow fruit and vegetables, although many also raise cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs.

Malta’s CAP subsidies show a strong focus on animal products.

This is not unique to Malta and has been criticised by four major environmental networks in a joint report, where they argued against the use of CAP funds for “on measures that encourage large-scale unsustainable farming”, notably livestock, across the EU.

Chicken farmer Emanuel Ciappara is the private farmer to be allocated more than €1 million in CAP funds during the current financing period. He is also the largest beneficiary of the Maltese CAP’s “On-Farm Productive Investments”.

His project, an “Investment in new state-of-the-art broiler production facilities and ancillary machinery”, is estimated to cost over €2 million out of an indicative budget of €10 million for this measure.

A lawyer representing Ciappara and his companies said he is “a self-employed poultry breeder and he personally operates a poultry farm, breeding poultry, in his own personal name, separately and distinctly from [a separate beneficiary] C & K Ciappara & Sons Limited” – the funds received are “to upgrade and expand his poultry breeding operations”.

The dairy sector is considered to be strategically important to Malta, maintaining stable milk production since Malta joined the EU despite the number of raw milk suppliers shrinking in half between 2003 and 2019.

Malta Dairy Products, the owner of the Benna brand and a ‘quasi-monopoly’ of fresh milk, was allocated over €450,000 in EU subsidies during the current period.

Data provided by ARPA shows that over the current period, 223 eligible applications from dairy farms, 226 from sheep farms, 85 from beef farms and 29 under a livestock measure were received.

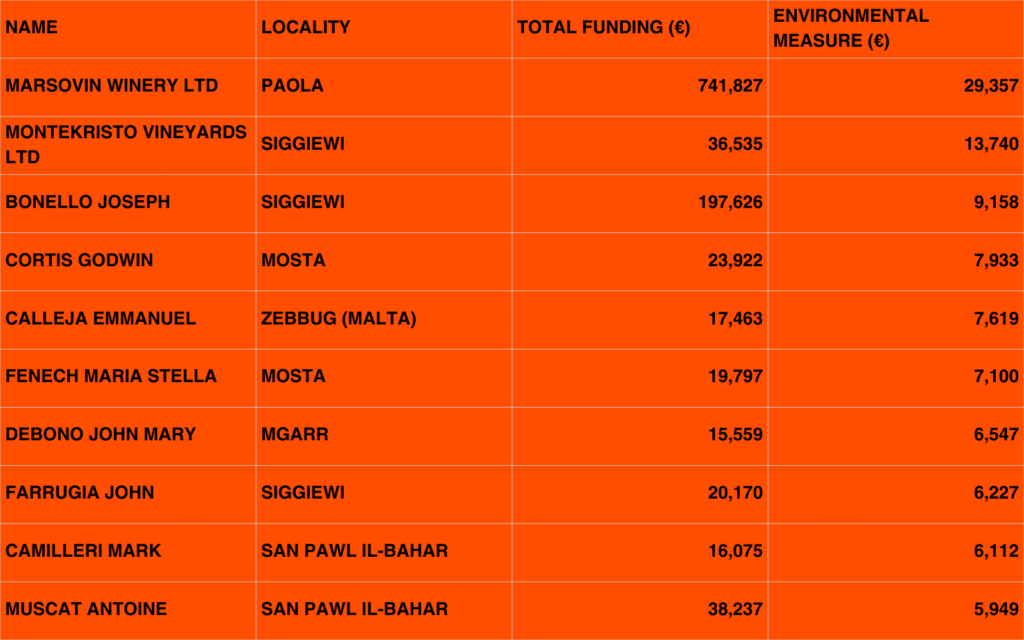

Wines benefit from CAP’s environmental measures

Vineyards are the largest recipients of funds and measures designed to pay farmers directly for environmentally beneficial practices, a part of CAP’s focus.

According to ARPA’s data for the current funding period, no farmer applied under the biodegradable mulch measure, only eight applied under the biodiversity scheme, 124 applied under the integrated pest management scheme, and 11 applied under the organic farming scheme.

Montekristo benefits from CAP despite irregularities

One of the largest recipients is Montekristo Vineyards Ltd, established in 2003, and owned and run by Carmel (known as Charles) and Paul Polidano.

Montekristo received agricultural subsidies in 2023 and 2024, after the Planning Authority had issued enforcement notices for illegal building in an agricultural area on this site, which also features a concrete plant and a batching plant.

Charles Polidano’s 2009 and 2010 applications to sanction Montekristo’s family park, including an illegal zoo and an extension of its winery, in Siggiewi, were approved by the Planning Authority in July 2025 despite pending court cases concerning the site.

Wine making on the site can be traced to 2005, when the group obtained permission to convert a pig farm into a winery and vineyard, and later to expand it. However, case files indicate that the area used for winemaking was to be limited.

Today, Montekristo is identified as one of Malta’s main wine producers. In 2014, the Times of Malta reported that it had already received agricultural subsidies intended for farmers in disadvantaged areas.

Montekristo group did not respond to repeated attempts to reach it for comment.

What the people wanted

The latest EU regulation on CAP acknowledges that “Member States should have the option to design a specific intervention for small farmers replacing the other direct payments interventions”.

Yet, international NGOs have noted that “the EU’s CAP has largely failed several of its objectives. It failed farmers, who continue to leave the sector en masse and are hit by one crisis after another. It also failed to address environmental issues, and in some cases even exacerbated them”.

A survey among Maltese residents found that nearly all consider agriculture important for the future, yet an overwhelming majority would sacrifice EU agriculture’s competitiveness to fight climate change.

Nearly a third — more than the EU average — hold farmers responsible for protecting the environment, and half are ready to pay more for climate-friendly products.

Against this backdrop of criticism, public concern and policy reform, the debate over CAP’s future remains far from settled. While many farmers continue to struggle financially, expectations of the sector — particularly on climate and environmental protection — are only increasing.

“Farmers are living in economic poverty, but are rich in other ways,” Cane Vella concludes.

This investigation is part of Senza Segnale, a collaborative project that reconnects news deserts in the Mediterranean.

Senza Segnale is a project by Amphora Media and IrpiMedia, in collaboration with Fada, Facta, Indip, Infonodes, Centro di Giornalismo Permanente, in cooperation with the Allianz Foundation.

Giulia Bonelli (Facta) contributed reporting. Rui Baros contributed data scraping.