By Daiva Repečkaitė

Wax paper from your sandwich. Delivery containers. Wet wipes. Frayed, low-quality leggings from a fast-fashion app. Many daily-use items become waste that cannot be recycled. The proposed solution: a waste-to-energy facility at Magħtab.

But is it the most effective way out of the country’s waste crisis? An analysis of available waste treatment solutions shows that all of them have limitations.

Will it absolve Malta of recycling obligations?

Landfilling, which means dumping waste in the ground, is Malta’s most common but costliest waste management method given the country’s space limitations.

Malta is under pressure from the EU to reduce landfilling of waste. The country relies on waste export, so the plan for new facilities also aims to increase the country’s self-sufficiency.

In addition to the energy-generating plant, a thermal treatment facility (which ‘cooks’ waste at high temperatures to undo its hazardous properties) is planned within the same complex, replacing the one currently operating in Marsa. The two facilities are different and serve separate waste streams.

In a 2018 technical report, then-Minister for the Environment Jose Herrera called the government’s commitment to setting up a waste incinerator a “bold” decision.

“This was an environmentally responsible decision and will not affect our ambitious objectives to increase our recycling efforts in order to meet the 2030 recycling targets,” he stated in the foreword. The report noted that UK islands, such as the Isle of Wight and the Isle of Man, had waste-to-energy facilities.

A 2016 study found that exporting waste to other EU countries for processing would cost tens of millions of euros every year.

The incinerator plan faces criticism. For example, in a public consultation, Friends of the Earth and Moviment Graffitti wrote that “building a Waste to Energy Plant was in no way a ‘green’ solution”.

“A lot of people will think of the incinerator as a quick solution. It’s not, it requires a lot of planning, a lot of money,” says Dr Margaret Camilleri Fenech, who researches waste management at the University of Malta.

She warns of the so-called rebound effect – people waste more when they know that mitigation measures are in place.

“I am scared that we’ll shift into that [mindset], but we still have recycling targets to respect, which we’ve never managed to anyway,” she says, adding that Malta will not likely to be able to use the incinerator to dig up old landfilled waste and clean up former landfilling sites, because it is mixed with construction waste.

“We have a high level of construction waste, for example. Obviously, we cannot burn it. And our organic fraction has a lot of food waste. There’s a lot of water content, so obviously you need to dry it up to burn, and we still need to respect the recycling target of the EU,” she says.

Insufficient capacity to prepare waste for recycling

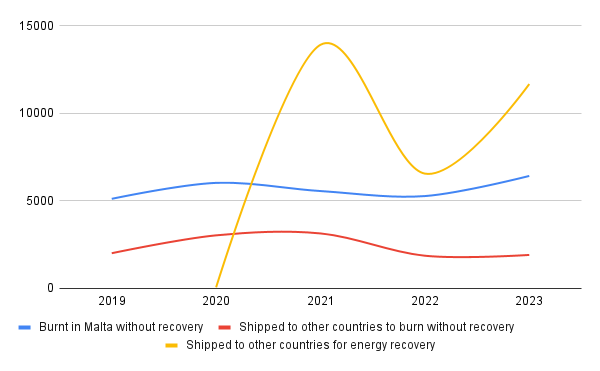

Malta ships its waste to various countries. Figures from Eurostat, the EU statistical agency show that Malta shipped over 14,000 tonnes of paper and cardboard to India, over 1,200 tonnes of plastic to Türkiye, and over 1,200 tonnes of synthetic waste textiles to the United Arab Emirates. Data shows that some of Malta’s waste is already burned for energy, but again, abroad.

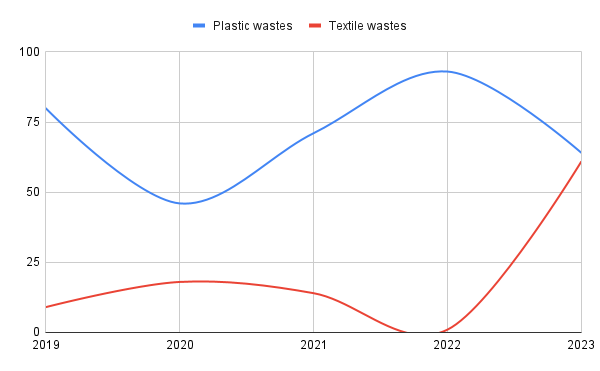

The probability of recycling recyclable materials, such as plastic, depends on how clean they are when they arrive at the point of waste separation. A 2021 audit reveals that focusing on plastic is crucial. In Malta’s case, plastic destined for recycling is not clean at all.

The audit found that “Malta lacks the infrastructural capacity to engage in more comprehensive and sustainable waste management” and that, at the time, only around a tenth of all plastic collected was being recycled, while two-thirds were landfilled locally.

It further explained that incineration (burning) with energy recovery would be preferred to landfilling when it comes to dealing with plastics rejected for recycling and plastics that residents and businesses threw into the mixed waste bags – these were not separated and considered for recycling “due to the non-availability of operational capacity”.

New schemes will divert some waste

In 2023, waste separation became an obligation for individuals, companies and the government, subject to penalties.

Differentiated gate fees for disposing of waste at specific sites also discourage the delivery of mixed waste, as this is more expensive. Incentives to bring reusable cups for drinks were supposed to be operational since 2022 but remain rare.

In 2024, Circular Economy Malta, a government agency, introduced a scheme to encourage shops to offer discounts or other benefits to users who bring their own containers.

The agency claims that this initiative has successfully prevented the use of 63,524 single-use containers. However, 54,966 of them (87%) were detergent containers – typically made from sturdy plastic and recyclable. Existing reuse options do not address the issues with filmy and dirty plastic, or mixed materials.

According to Friends of the Earth Malta, an environmental NGO, “The [waste management] problem has been exacerbated in recent years by the country’s growing population, the tourism boom, and the “growth at all costs” mantra.”

“The tourism industry produces so much waste, when we look at the figures. Most of the time, we’re looking at how much money the tourism industry is bringing in. Still, we don’t look at how much waste they are producing, at how much water they’re consuming, energy, congestion, and we should balance these things out,” Waste researcher Camilleri Fenech added.

In response to a parliamentary question in January, Environment Minister Miriam Dalli said that the waste-to-energy plant will process 40% of Malta’s non-recyclable waste and provide 4.5% of the country’s energy needs.

Malta’s consumer and tourist economy creates a demand for easy waste solutions. Currently, dumping most waste into landfills and shipping it abroad serves as such, but this practice will be increasingly regulated and expensive. Years of explaining to people and, crucially, companies about how to do the right thing have achieved very limited results. Given Malta’s growing waste generation, the mountain of waste is being treated as one of the most reliable renewable energy sources.

Leave a Reply