By John Cordina / Newsbook

This is one of two stories about two vastly different Mediterranean communities struggling with overtourism produced through the collaborative project Senza Segnale, involving journalists from Malta and Italy. One focuses on a lively city and tourist destination – Palermo – but this one is about my suburban hometown of Swieqi, a place with little to offer tourists yet deeply impacted by tourism nevertheless. Published in collaboration with Newsbook.

The Suburbanites’ Protest

A few dozen people who gathered in Swieqi on the last Sunday of August ensured that Malta joined tourist destinations across southern Europe in protesting against overtourism last year, though the choice of venue may seem strange to outside eyes.

Swieqi, which emerged as a fast-growing suburb of neighbouring St Julians in the 1960s, is far from a tourist destination. Home to over 15,000 people, it has no beaches, no notable attractions, few venues for socialising. Two hotels were torn down years ago, and the only collective accommodation left are an aparthotel and two guesthouses with around 80 rooms among them, with planning policies that effectively preclude the development of new ones.

Calling Swieqi boring is not unreasonable, but it is centrally located on a small island and is widely considered a desirable place to live. And boring means quiet; or at least it used to.

The Holiday Flat Loophole

But Swieqi’s restrictions on touristic development have been rendered worthless by a phenomenon that has transformed tourism: a sharp rise in holiday rentals, fuelled by rise of Airbnb and other online platforms making them readily accessible to travellers across globe.

It is a phenomenon that caught authorities unprepared, as Swieqi itself shows: while it is mostly designated as a “residential priority area” in which tourist accommodation is prohibited, holiday rentals are still treated as ordinary residences under Maltese planning law.

Any home can thus be turned into licensed “holiday premises,” circumventing policies drawn up before a flood of tourist rentals could have been foreseen.

A complex of holiday flats on Swieqi Road is but one example of this anomaly: it was built after a planned guesthouse was refused a permit as it was deemed unsuited to a residential area.

This road has become a hotspot for holiday rentals as it leads straight to Malta’s main nightlife district of Paceville: an underpass beneath the Regional Road, one of Malta’s main roads, is all that separates the two.

Many listings emphasise the proximity to Paceville: some do not even mention Swieqi at all.

Worse than Barcelona

Official statistics present an unenviable scenario for Malta and Swieqi: the proportion of tourist rentals is markedly higher than in the city notable for fighting back.

Barcelona, home to nearly 1.7 million people – roughly three times Malta’s population – had just over 10,000 licensed tourist flats in 2024, when its mayor confirmed they would be banned for good by 2029.

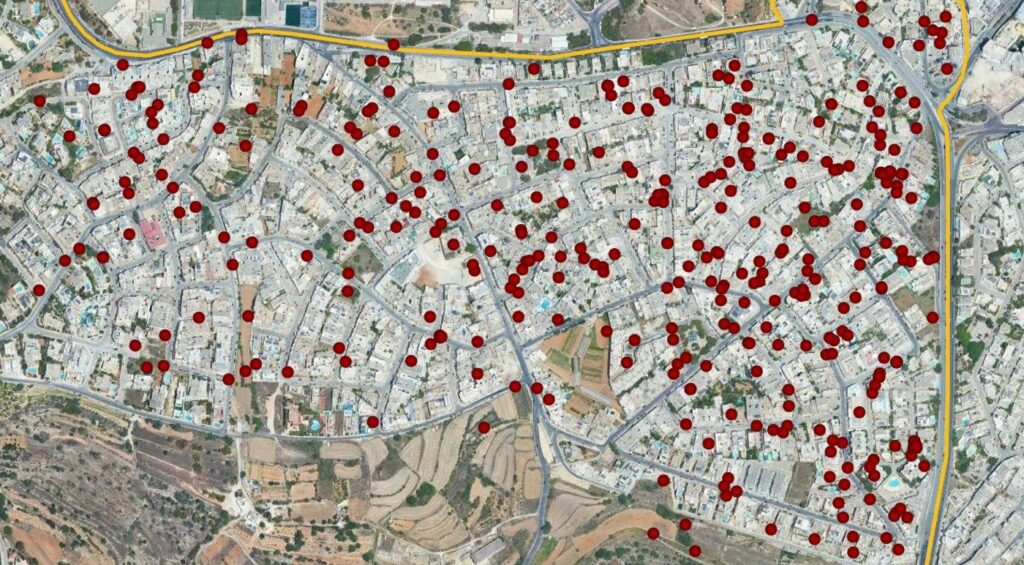

The number of licensed holiday premises in Malta reached 7,649 by the start of February, and Swieqi – home to 2.7% of the national population – hosts 5% of them, with 386 licensed premises providing 2,079 bed spaces.

Actual numbers may well be considerably higher when unlicensed premises are taken into account: an exercise carried out last summer identified 432 active Swieqi listings on Airbnb alone.

Malta thus has more than twice as many short-term rentals per capita – and Swieqi roughly four times as many – as Barcelona, despite national tourist numbers that still fall far short of what the city receives.

No Slow Season

Malta’s tourism numbers are growing rapidly, as is the case with many other Mediterranean destinations, facilitated by low-cost flights and holiday rentals which have helped make travel more accessible.

Tourist numbers had been stable for around two decades until the early 2010s, with Malta welcoming a little more than 1 million tourists a year, but have risen dramatically since.

Malta welcomed more than 2 million tourists in 2017, and the 3 million mark was surpassed in 2024, with 3.56 million travellers. That record was surpassed by November 2025, and the country may well have surpassed the 4 million mark by the end of the year: three times as many as it had received just 15 years prior.

Consequently, while tourism in Malta remains seasonal, peaking in summer, one cannot really speak of a “slow” season anymore.

No less than 200,000 people visited Malta in February 2025, in what is historically the slowest month of the year.

Given these figures, it is perhaps unsurprising that all Swieqi residents I spoke to suggested that the situation took a marked turn for the worse around a decade ago.

“It doesn’t end now: it’s slightly less intense, but it’s continuous,” Arnold Cassola, who organised the August protest in which he decried Swieqi’s transformation into “Paceville’s daytime dormitory,” explains. “You could plan around July and August before, but it’s not like that anymore.”

Noise disturbances are a regular complaint, whether through house parties from partygoers walking to or from their flat, often while drunk or intoxicated. This foot traffic often leads to other nuisances, including vandalism and the odd fight. Garbage is another chronic concern: the waste generated in tourist rentals is often brought out at inappropriate times, and often remains uncollected for days.

The Council’s Crusade

Given the chance, Swieqi mayor Noel Muscat would likely follow Barcelona’s lead and ban short-term rentals outright: a proposal by the council he leads would effectively do so. But Maltese local councils have no authority to do anything of the sort on their own.

The lack of powers – limited since they were created in 1993, and reduced further over time – is an evident source of frustration for Muscat, not least since the local council bears the brunt of complaints it cannot directly address. Tourist accommodation licensing is under the Malta Tourism Authority, and local councils can no longer set waste collection schedules after a single national schedule was introduced.

What they can do is speak up, express their concerns and present proposals, and while the local council has done so, it is futile if the authorities prove unwilling to respond. This is laid bare by a document Muscat provides: a letter prepared for a meeting the council held with the minister for tourism a full decade ago, on February 2016.

In that letter, Muscat highlighted that the number of short-lets had “mushroomed” in Swieqi, causing its inhabitants stress “in the form of noise disturbances, sometimes vandalism and even cleanliness,” and pleaded for regulations that would make it possible to maintain order and address abuse.

But this plea went unheard, with Muscat observing that if short-lets were mushrooming then, “now they’re spreading like wildfire.”

It went a step further last year, presenting no fewer than 12 proposals, including requiring tourist rentals to be classified more accurately as commercial properties. The council also called for a moratorium on new licenses until carrying capacity studies are conducted and for strict limits to be set on the number of tourist rentals in every Maltese locality.

The Protest Organiser

Few people have lived in Swieqi as long as Cassola, an academic and veteran politician who presently chairs the political party Momentum: his family had moved to what was then a nascent suburb in 1972, when he was a teenager. He moved back to his late parents’ home a few years ago, after spending much of his life in a nearby apartment, a move which gives him some space from short-lets, in contrast to his former apartment.

But it’s still very close to Paceville, and his street sees considerable foot traffic accordingly.

Beyond countless incidents of drunk partygoers urinating at his doorstep, he’s had a car mirror broken no less than three times.

Through his Facebook page “Arnold’s Citizen Watch,” he regularly airs the grievances of people from around the country, so it is perhaps unsurprising that he is involved in his hometown’s struggle against overtourism.

His efforts have included launching a parliamentary petition calling for urgent action on the “misuse of tourist rentals in residential areas,” which attracted 2,373 signatures, but he felt a protest was necessary as summer arrived and tempers flared.

In part, Cassola was inspired by growing community activism in Swieqi and beyond: he made a point of inviting residents’ groups from other areas similarly bearing the brunt of overtourism. But the protest was also organised in response to growing anger and in a bid to pre-empt plans for more disruptive actions, which he feared would backfire, including a proposed protest which would have dumped rubbish bags outside the prime minister’s office to highlight Swieqi’s own garbage crisis.

The Former Minister Claiming Maladministration

Another prominent community voice which emerged in the summer was Evarist Bartolo, a government minister between 2013 and 2022 as part of the governing Labour Party and a Swieqi resident for over 30 years. A former journalist and lecturer in journalism – my thesis supervisor, as it happens – Bartolo has now drawn the curtain on his political career, but like Cassola, maintains an active presence on Facebook, regularly sharing his reflections. He readily endorsed the protest, and while was unable to attend it, prepared a message which was read out on his behalf.

As far as Swieqi residents are concerned, Bartolo and I can both count ourselves lucky: neither of us are particularly affected by holiday rentals, even though his home is closer to Paceville than mine. Still, he is regularly approached by fellow residents hoping he could be their voice, often Labour supporters in what is a stronghold of the Nationalist Party, which has enjoyed a strong majority at the council since its inception.

Bartolo has no compunction about calling out his former colleagues in government as the stories pour in. He is adamant that the authorities have been guilty of maladministration in managing tourist rentals, and has asked the Office of the Ombudsman to investigate accordingly.

As one example, he takes aim at the very structure of Malta’s tourism authority, which has the dual – and seemingly conflicting – role of regulating and promoting the tourism industry, with much of its budget funding the latter aim.

Bartolo observes that other tourist destinations have shown that it was possible to act decisively against overtourism: some may even have gone too far in their opinion. But in Malta, the authorities continued ignoring the issue at their peril.

“If I were them, I would worry about allowing an irresponsible sector to harm the reputation of tourism,” he insisted. “Because hostility to tourism will only increase.”

Suffering in Silence

A common thread emerges in my interviews with three of Swieqi’s most prominent political figures: a reluctance by many residents to go public with their concerns. Even August’s protest attracted a modest crowd of around 80 people, though that may in part reflect political bickering which ultimately saw the local council sit it out. Cassola hailed these numbers as a “very good result” nevertheless, noting that Swieqi was still unaccustomed to community activism.

Muscat, on his part, had highlighted that many residents were “suffering in silence,” and in September, the local council provided the community with another opportunity to speak up through a meeting with the community policing team responsible for the area.

With dozens of people turning up, turnout was good as far as Maltese community meetings go, and the crowd had a lot to say. But it emerged that just eight police reports had been filed for tourism-related disturbances during the year.

“We know how serious the situation is,” Inspector Gabby Gatt, who manages the community police teams in Swieqi and a number of other localities, assured the residents present. “But we do not receive enough reports to substantiate it.”

As the meeting progressed, however, and as one resident after another spoke up, a clear pattern emerged: the resources the police could or wanted to allocate were nowhere near what residents were hoping for.

And an incident shared by Gatt highlighted that landlords have little incentive to ensure their guests are good neighbours: one informed about his rowdy guests celebrated that he could now claim their deposit.

Enter the Pressure Group

The community police were not alone in encouraging residents to file reports: the same message is emphasised in “Swieqi Pressure Group.” Though just a group chat on WhatsApp, as its moderators make clear, in a locality that lacks a residents’ association of its own it may come closest to filling that gap for now.

It was established only last May: Cassola had observed that this took place amid rising tempers.

Martin and Steve (not their real names) confirm as much when we meet, but Martin recounts that the direct trigger was an incident which occurred near his home: a male tourist who took a naked morning stroll, aggressively confronting a number of residents along the way. A photo of this incident made the rounds on social media and was even featured in local press: Martin witnessed it in person.

“Things were already bothering me, then there was this case… the very next day it was done,” he said.

The authorities did respond once the incident went viral, even if Martin was less than encourage by the outcome: a suspended sentence after the tourist admitted to charges including harassment and public indecency. This, he stressed, would have no bearing on someone who does not actually live in the country.

The two men firmly rejected the suggestion that the community’s issues centred around numerous low-level offences which could not be considered a police priority, despite the inconvenience they may cause.

“There is a perceived sense of threat within the community, especially among the elderly and the young,” Steve observes. “I won’t say that people are afraid to leave their homes all the time, but the fear is there.”

Martin readily concurs, emphasising his fears about the safety of his two daughters, both in their twenties.

An Inadequate Response, By Design

The interview with ethe two men took place the day after the community police meeting, and confirmed that their suggested remedy had its limitations, as Steve found out when he reported a loud flat party keeping his family awake the night before his son took an exam.

“I go out, literally screaming, file a report, but they keep going,” he notes. “By the time the police arrive an hour later, they are knocked out, and there’s nothing to report.”

The meeting saw Cassola repeatedly challenge the police’s insistence on reports: they could and did act on their own initiative when they saw fit. He recalled another incident involving a naked tourist, one filmed riding a motorcycle through Malta’s streets and was later identified, prosecuted, and fined after the footage went viral.

Various residents made clear their reluctance to follow through with a report publicly, including by testifying in court: not least since it would mean facing off against the business interests behind the holiday rentals. Neither they nor Cassola swayed police from insisting on the necessity of doing so, however.

Bartolo viewed this insistence cynically, deeming it a deliberate tactic.

“They insist you must show up and testify deliberately, to make you give up,” he observes. “Why are we expecting ordinary individuals to step up? Why don’t the authorities do anything to strike a balance and protect the public?”

‘Collateral Damage’

In this context, the residents’ dealings – or lack thereof – with police and other authorities highlight that Swieqi’s struggles were not an issue of residents versus tourists, but of a community burdened by a business that often profited at their expense. The link between short-term rentals and Malta’s politically-influential construction industry is not missed by anyone I spoke to.

“The government is closing an eye… to let people turn a profit,” Martin muses. “And we are just collateral damage.”

He suggests a simple remedy – “if you’re not capable of handling your clients, close it down” – but it is not an approach the authorities are exactly known for where business interests are involved.

Muscat’s own assessment is that the state’s failings were not a matter of incompetence, but betrayed an unwillingness to act.

“You’re under pressure… and you have to stand up to it,” he notes. “But they give in.”

And as our interview draws to a close, he warns things can get much worse.

Profiteering Over Everything

“Developers have become dangerously strong, you have no idea,” he maintains. “They view us as mere ants, and they don’t know how to invest in anything else.”

The present short-let craze was a natural consequence of this, the mayor maintains: they became the most profitable use of an apartment. Consequently, in a country where apartments are often sold before a permit is even issued, there are now projects that are not being advertised for sale at all, including a large apartment block being built a short distance away from the local council offices that could by itself increase Swieqi’s stock of licensed holiday rentals by nearly a third.

“Spain was exactly in the same situation Malta is in now before the 2008 crisis,” he observes. “The economy was thriving, but it was all built on property. And what do we invest in? Property, property, property, property…”

Bartolo expresses similar sentiments as he rails against an attitude that prioritises profiteering over all else, and warns that change is unlikely when Malta’s main political parties are financially dependent on businesses.

“The scales will always be tipped in favour of the donors,” he muses. And as Muscat had done, Bartolo warns this may have dire consequences down the line.

“I worry that we’re being very short-sighted, because we’ve always scraped through,” he observes. “So we remain on the brink.”

The Government Responds

With the interviews taking place as summer was drawing to a close, it was perhaps inevitable that they betrayed a general sense of pessimism about the future of the community.

“If the authorities fail to take proper steps, it will be more of the same,” Bartolo maintained. “And so far I’m not seeing any political will.”

The others shared similar sentiments amid expectations that the growth holiday rentals would remain unchecked, though Cassola did temper this pessimism as he hailed the fact that Swieqi residents were finally finding their voice.

And by the end of summer, their voice had reached its intended audience.

In September, the government picked Swieqi and Valletta for a pilot project which aimed to develop community solutions to the problems caused by overtourism. And in November, this was followed up by proposed regulations which would make it possible to restrict short-lets to designated areas and require tourist rentals to display a 24-hour contact number which aggrieved residents could complain to.

A month-long public consultation finished in December, though the regulations are yet to become law, and the number of holiday rentals in Swieqi and in Malta has only grown since then.

A Hopeful Future?

The proposed regulations still fall considerably short of the local council’s demand, with no caps on numbers, no indication that existing rentals would be affected and no commitment that any designated zones would be drawn up. And in a country that has long struggled with enforcing regulations, their implementation still relies on the political will Bartolo failed to see among his former cabinet colleagues.

Bartolo’s response as I sought to find out whether the government’s gestures had given my interviewees new hopes was succinct: “The proof of the pudding is in the eating,”

Muscat was hopeful: “there is no reason why (the situation) should not improve… God forbid that it does not improve drastically.” But the mayor emphasises the need to do more, not least closing the planning loophole that enabled Swieqi’s transformation into Paceville’s dormitory and a capacity study, whilst warning that the challenge will be even greater this year.

The others do not share his optimism, with Cassola viewing the proposals cynically as “lip service to gain votes, since elections are approaching.” Any sign of progress, he maintains, could only be determined after the next election – which must take place by 2027 – takes place.

Steve and Martin, meanwhile, see little cause for celebration since even winter has not brought them peace: it’s still bad now, only better than summer.

Noise, disturbances, garbage accumulation and drug use continue unabated.

Neither are yet to see any political will to change things: “if there was, things would have moved in the right direction,” Steve muses, while Martin reiterates that the interest of those profiting at the community’s expense were still being put first.

This scepticism does not appear unwarranted, given that a previous proposal to require apartment owners to obtain approval from their condominium neighbours before licensing it as a holiday rentals was ditched early last year: tourism minister Ian Borg deemed it unfair on those who invested in short-lets. Instead, Borg pledged to enforce the rules to ensure neighbourly respect.

As Swieqi can attest, that proved to be a broken promise, one that casts a shadow on the latest pledges. But it also led to a community still struggling to define its identity to find its voice and be heard, across the political spectrum: the next step, perhaps, will be to ensure it is actually listened to.

This investigation is part of Senza Segnale, a collaborative project that reconnects news deserts in the Mediterranean.

Senza Segnale is a project by Amphora Media and IrpiMedia; in collaboration with Fada, Facta, Indip, Infonodes, Centro di Giornalismo Permanente; in cooperation with the Allianz Foundation.

Leave a Reply