- Malta’s 2025 trapping season has reopened under a “research derogation” allowing trappers to act as licensed researchers despite an EU court ruling that Malta failed to prove no scientific alternatives exist.

- Malta’s latest legal notice erases the official ringing coordinator, EURING, and potentially opens up the ringing license to trappers.

- Government claim: Trapping is “the least intrusive method” to collect data on finch migration. The FKNK defends the derogation as merging “socio-cultural tradition with research”.

- Over 4,000 trappers have reportedly recorded only 40 ringed finches in 2020-2023, many of which were caught in Malta. EURING, Europe’s bird-ringing authority, says the data “does not meet acceptable scientific or ethical standards.”

- Government-hired scientists called the trapping derogation results “not directly comparable” with scientific analysis.

- Malta’s enforcement capacity has declined, the number of vehicles used for field checks has halved between 2022 and 2023, and Gozo remains poorly policed.

- Licensed trapping areas overlap with Natura 2000 protected zones, and inspectors report vegetation clearing and habitat damage.

- Both conservationists and independent experts, including a former Ornis Committee chair, say the derogation is a guise to legitimise traditional trapping, not a genuine scientific effort.

- The European Commission’s infringement case remains open. Malta could face financial sanctions for failing to comply with the Court of Justice ruling.

Malta’s 2025 trapping season is now open.This year, the government has relaxed rules on scientific bird ringing, removing references to EURING, the coordinating body of bird ringing schemes. The state insists the trapping effort is for research despite the EU Court of Justice ruling that Malta failed to prove a lack of alternatives.

The government’s decision has split both sides of the trapping debate: the National Association of Hunters and Trappers (FKNK), the leading hunting and trapping association, Kaċċaturi San Ubertu (KSU), a smaller NGO, and conservation NGOs.

“This historic step opens a new chapter in our country’s approach to bird conservation and research,” FKNK said.

KSU’s secretary Adrian Cauchi emphasised that no formal ringing course exists in Europe, and all ringers must ultimately be allowed to operate by the government.

“I cannot do the [training to become a ringer] with Birdlife, because Birdlife is with EURING. EURING is not giving us a way out because it wants to abolish the traditional methods,” he told Amphora Media.

For Birdlife Malta, this “ill-conceived plan is destined to fail. Scientific bird ringing is only credible when carried out within the EURING network, the only recognised European framework for bird ringing. Any attempt to operate outside this network will produce meaningless data and expose Malta to further ridicule and sanctions.”

Trapping continues to court controversy, but the question is: Is trapping in Malta really all for research?

Malta’s government began declaring research derogations for trapping in 2020. Maltese law allows “under strictly supervised conditions and in a selective manner, a research derogation to obtain scientific data on Malta’s reference population of the seven finch species”.

The legal notice argues that “ornithologists and licensed bird-ringers have been unsuccessful in collecting […] the required data to meet the stated objective of the Finches Research Project,” which is:

“Where do finches that migrate over Malta during post-nuptial (autumn) migration come from?”

Police spot-checks within each region are promised to be daily.

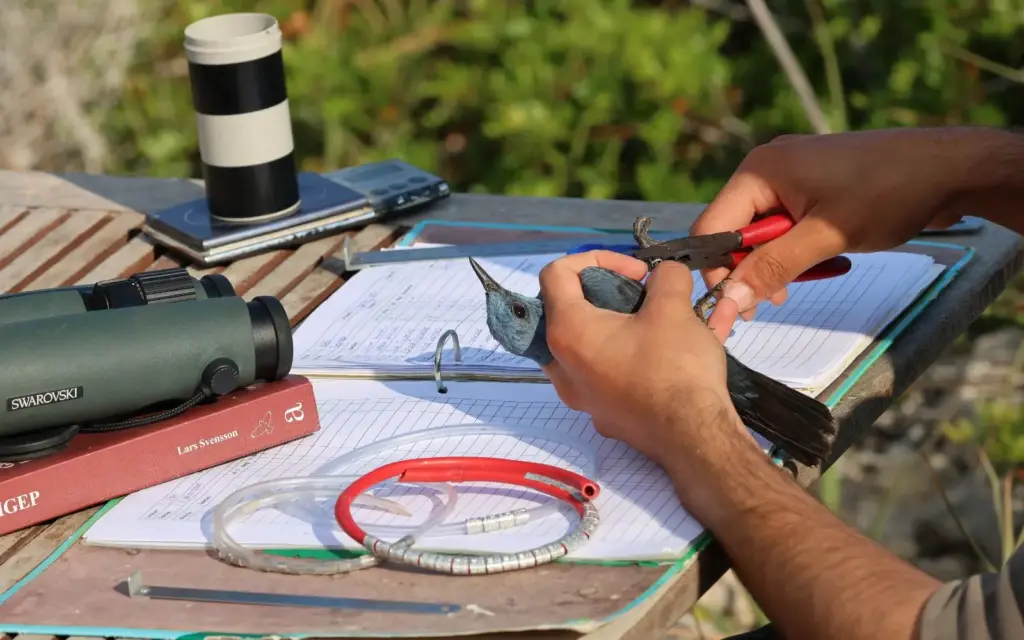

The Wild Birds Regulation Unit (WBRU), under the Ministry of Gozo and Planning, explained in 2021 that trappers can “control”, or temporarily capture, the seven finch species, “determine which are fitted with a ring”, and immediately release them.

“Once data saturation has been reached for all seven finch species, the research project will terminate in its entirety,” WBRU said in 2023. The government considers that “data saturation may be reached at a threshold of 60 ring recoveries per species”.

The Ministry for Gozo has claimed it is “the least intrusive course of action to gather quality data on the provenance of migratory finches.”

“This initiative is generating robust information, including a significant increase in foreign ring recoveries through the clap-net system, which in some species has even surpassed existing information. In five years of such research, the information collected from ring recoveries exceeded 100 years of ring recoveries by BirdLife Malta. This information is essential for calculating the populations of these bird species,” the ministry said in a press release.

FKNK has argued that the derogation combines “deep socio-cultural traditions with scientific research” and that banning the practice risks “the potential for stagnation in the field of ornithological research”. Its president thanked the government for allowing the ‘continuity’ of the practice.

In 2024, FKNK published a series of claims regarding the research project and EURING, the European coordinators of bird ringing schemes. These included:

- Trappers’ nets are more effective than ringers’;

- Each bird is screened for a scientific ring;

- “EURING and the local monopoly of bird-ringing made it challenging to persuade impartial candidates (…) to endorse the Project.”

- “Throughout the open hunting and trapping seasons, the Maltese islands are effectively under police control.”

Conservation NGOs have a different view.

“Trapping is an unsustainable method of hunting which causes damage to wildlife and habitats,” Birdlife Malta has said, adding elsewhere that the traditional trapping method destroys natural habitats, harms non-target wildlife, and fuels illegal wildlife trade.

“In a last-ditch attempt to justify this discredited scheme, Minister for Hunting and Trapping Clint Camilleri, supported by Minister for the Environment Miriam Dalli, has enacted amendments to the Conservation of Wild Birds Regulations that would significantly dilute the standards for scientific bird ringing,” the NGO said.

The NGO Committee Against Bird Slaughter (CABS) claims that, “Many bird trappers did not comply with the law even before the final finch trapping ban and either laid out their nets in spring or used electronic decoy callers. (…) Police controls are rare, and court decisions against the few convicted bird trappers are usually at the bottom of the penalty line”.

Timeline of events:

1st May 2004: Malta joins the EU. The EU’s legislation on wild bird conservation became binding, but Malta is allowed to phase out finch trapping and replace it with a captive breeding programme.

2008: Arrangement expires.

2009-2013: Trapping is prohibited in Malta.

2013: FKNK submits a request to reopen trapping season following the change of government.

2014: Government reopens trapping season in autumn.

2018: The European Court of Justice issued the first ruling on Malta’s finch trapping practice. In its ruling, it said that the government did not prove that no alternative solution exists and that insufficient evidence meant arguments that trapping affects a small number of birds could not be substantiated.

2020: Malta’s government started declaring research derogations for trapping.

2024: EU court issues ruling on research derogation, finding that Malta’s authorities did not prove a lack of viable alternative, and “there is no mention of other standard scientific means of research in the ornithological field”

2025: Legal notice 251 removes a requirement for rings to only be obtained from bird ringing schemes approved by EURING. Trappers now allowed to use live decoys.

The European Commission’s infringement case against the research derogation remains active. The Commission has sent a letter of formal notice for failing to comply with the judgement. The Commission may decide to refer Malta back to the Court of Justice of the European Union, with a request to impose financial sanctions. The Commission’s spokesperson said, “The Commission is assessing the available information before deciding on next steps”.

Does the derogation follow a research methodology?

Official bird ringers, under the EURING umbrella, ring finches in the countries where they breed. The WBRU argues that the birds are not followed as they migrate, and the Maltese “research project is what renders the effort invested by bird-ringers in other countries to ring finches worthwhile”.

To participate in the scheme, trappers must check for scientific rings, a process called ‘control’.

Participating trappers are “instructed and examined on the procedure”, and captured finches are “immediately released unharmed back into the wild”, “including those that are “not fitted with a scientific ring or satellite-tag”.

In Malta, bird ringing was previously carried out by Birdlife Malta, the only partner of EURING. The legal notice now allows licensing & ringing from any “qualified trainer who is part of a bird ringing scheme”.

In a December 2024 statement, EURING said that the Maltese trapping research project “is unlikely to provide useful scientific data on a reasonable timescale, and that the poor-quality data being gathered does not meet acceptable scientific or ethical standards.”

“The intensity of finch trapping that is being undertaken is likely to have major impacts on bird movements and behaviour, and is therefore not compatible with studying the natural movement patterns of these species,” it continued.

Nicholas Galea heads Birdlife’s EURING-approved ringing scheme in Malta, with 29 licensed ringers on the islands. According to the government’s 2023 report to the European Commission, Birdlife ringed 20,847 birds in 2023.

“We are not against research, but we are against the use of research as a disguise,” he told Amphora Media, confirming that in previous seasons he verified the trappers’ information on ringed birds after it is passed to him.

“Data is always data, and information is information,” he said, adding that this does not mean he approves of the capturing method.

Amphora Media spoke to Kaċċaturi San Ubertu’s (KSU) secretary Adrian Cauchi. KSU “practices a policy of zero tolerance towards any hunting illegalities and vets all of its members prior to acceptance.”

“I would have expected EURING to jump on the possibility be there, supervise, offer their expertise and influence, as much as possible, to the legislator to carry out the best activities for the birds,” Cauchi said, adding “why not involve trappers if you really want to convert them, if you really want to ensure that you know exactly what they’re doing, why not get them under your umbrella rather than push them as far away as possible?”

In previous seasons, Birdlife declined government requests for ringers to accompany the trapping scheme, citing the disparity in numbers between trappers and ringers.

“With 10 trappers and ringers, it’s fine. (…) But [the government] always wants 4,000 trappers and one or two ringers, which means the others will always do what they want,” Galea said.

Amphora Media also spoke to Mark-Anthony Falzon, the former chairman of the Ornis Committee (2014-2017), an advisory board made up of hunters, trappers, conservationists and government appointees. In 2014, Falzon abstained from the vote on allowing the trapping derogation but defended the position. However, he is critical of the research derogation.

“To do research, you need researchers. (…) Trappers are not scientists. They are not trained in any scientific method. Bird ringers are not scientists either (…) but they follow the scientific method tightly regulated by EURING,” he said.

“For a trapper to release what they have just caught is unthinkable. It’s like winning the lottery and tearing up your ticket. (…) Some of these birds are highly prized.”

Have the trappers produced quality data?

A Wild Birds Regulation Unit’s 2024 report states that 4,105 General Licences for Live-Capturing of birds were issued.

In addition to collecting research forms filled by trappers, the WBRU commissioned surveys of migratory finches by two scientists with marine ecology specialisations.

One of the objectives was “to correlate migration data gathered through the present survey with bag data for the relevant species, should any live-capturing derogations or research derogation be applied during the autumn season of the contracted years.”

However, the authors said “the two sets were collected for different purposes, using very different methodologies, and therefore the magnitude of values are not directly comparable” which is required for “robust and rigorous assessment”.

For example, on some days, trappers caught over 200 common linnets and 50 common chaffinches. In contrast, staff at monitoring stations across Malta counted up to 10 common linnets and even fewer common chaffinches per day – sometimes none.

Malta submits yearly derogation reports to the European Commission. This is what the trappers have found over the years, according to these reports.

| Year | Ringed birds found | Notes about the birds |

| 2020 | 7 finches | 1 ringed by Birdlife Malta, others ringed in Hungary, Italy and Russia |

| 2021 | 15 finches | 6 ringed in Malta, others ringed in Italy, Slovakia, Greece, Hungary, Slovenia, Lithuania, Spain |

| 2022 | 1 finch | Ringed in Malta |

| 2023 | 17 finches | Ringed in Italy, Switzerland, Russia, Poland, Finland and Slovenia |

| Total | 40 finches | 8 finches ringed in Malta |

Reports to the Commission reveal that across thousands of trapping sites, trappers “controlled” only 40 ringed finches, and a fifth of them had already been caught by bird ringers in Malta.

A comparison with the government contractor’s data, suggests trapping hundreds of finches has resulted in very few ring recoveries, including only one in 2022. Trappers also send reports on rings that EURING was unable to verify.

EURING’s data Amphora had access to shows that out of 64 ring records submitted between 2020 and 2024, 18 had flaws: unclear country of origin, untraceable ring number, unknown scheme, or suspicious bird properties.

Fourteen birds carried a Maltese ring, but in several cases, trappers incorrectly recorded ring numbers. Ten of the birds had already been confiscated from trappers and apparently re-trapped.

“You can’t have 4,000 trapper-ringers all active at the same time in such a small country, because the same birds will be caught and caught all over again causing too much disturbance and stress,” Galea said.

“It’s difficult to decipher what people submitted. Sometimes they catch birds with our rings, and I cannot conclude which one it is. And really, what they’ve been discovering is that they’ve discovered nothing new.” Before trapping was outlawed, Birdlife Malta had already collected and published data on finches from trappers.

A search on Google Scholar for the listed finch species, the mention of Malta and WBRU did not return ornithology or biology articles, except for one that was about ticks in birds and was co-authored by Nicholas Galea.

KSU has implemented turtle dove satellite tagging projects, which Cauchi cites as an example of how traditional trappers can be retrained and benefit research. “The trapper was happy. The traditional method was kept, and this study and the research part was kept as well.”

The Ministry of Gozo and Planning did not respond to Amphora’s questions, and neither did FKNK.

Has the research effort reduced illegal trapping?

One of the conditions of applicable European laws for issuing derogations is that the practice must be appropriately supervised. But enforcement resources have been gradually reduced over the years, Malta’s derogation reports to the European Commission reveal.

The number of officers dropped from a maximum of 64 to a maximum of 53 between 2020 and 2023; as has the number of vehicles from 15 to 9.

| Year | No. of officers | No. of vehicles |

| 2020 | Minimum 53, maximum 64 | 15 |

| 2021 | Minimum 44, maximum 59 | 18 |

| 2022 | Minimum 42, maximum 56 | 18 |

| 2023 | Minimum 49, maximum 53 | 9 |

The EU’s court found that “In the context of Malta, characterised by a very high density of licence holders […] the fact that merely 23% of hunters have been subject to individual checks seems inadequate”.

The Malta Ranger Unit has recorded alleged instances of illegal trapping of protected species, use of illegal devices, and trapping outside the permitted hours. In a recent case, illegalities reported by the MRU led to a conviction of a trapper and cancellation of his licence.

Camilla Appelgren, from the MRU, told Amphora Media that officers often lacked training and coordination. At the same time, trappers allegedly had extensive networks of CCTV cameras and spotters to monitor NGO and police presence.

“There are times we don’t have any environmental police, and the district police don’t take environmental cases, so there is no one to call,” she said.

During the first days of the season MRU, Birdlife and police collaborated in an operation which led tthe o confiscation of illegally used equipment, including electronic bird callers, and unattended clap nets.

Gozo, meanwhile, presents a separate issue altogether. Data shows that contraventions are minimal compared to Malta. In 2023, there were 50 contraventions in Malta, compared to 12 in Gozo.

“With respect to hunting and trapping, it’s an open secret, really, that in Gozo, there is much less law enforcement, and police find it very hard to do their job,” Falzon added.

Galea and Appelgren warned that trappers inform each other of police presence, especially in Gozo”.

Enforcement Figures (Source: WBRU):

| Year | Contraventions on Malta | Unidentified suspects | Contraventions on Gozo | Unidentified suspects |

| 2020 | 23 | 11, or 48% | 6 | 5, or 83% |

| 2021 | 96 | 20, or 21% | 26 | 22, or 85% |

| 2022 | 56 | 6, or 11% | 3 | 3, or 100% |

| 2023 | 50 | 12, or 24% | 12 | 6, or 50% |

On 16th October, a trapper from Mgarr, caught in September 2022, was sentenced and had his trapping licence revoked for three years, CABS said in a press release. CABS members went to court as witnesses.

Between 2014 and 2024, the NGO’s reports resulted in 298 prosecutions for trapping illegalities. Out of those, 187 trappers were convicted, and “thousands” of birds were seized”.

Cauchi of KSU disagrees that policing levels are low. “You’ll see the police every day, twice, three times a day,” he said. His view is that illegalities are decreasing, but evidence collection methods have improved, and more of them make it to court.

“We should let authorities work and one of the key objectives is to ensure that trappers become researchers in their entirety. These things require a generational change. [An octogenarian] is a difficult person to change. I’m the next generation. I’m a converted man. I would very happily, very happily give all my [hunting and trapping] licences and just do ringing.”

He suggests that, contrary to popular view, KSU, as a hunters’ and trappers’ organisation practices discipline and enforcement internally.

“We don’t go and say these things on Facebook, but we do it in our own circles. The results speak for themselves in terms of targeting of protected species.” He would like to see court-mandated courses to rehabilitate perpetrators of illegal trapping.

Police spokesperson did not reply to Amphora Media’s questions.

Is trapping environmentally sustainable?

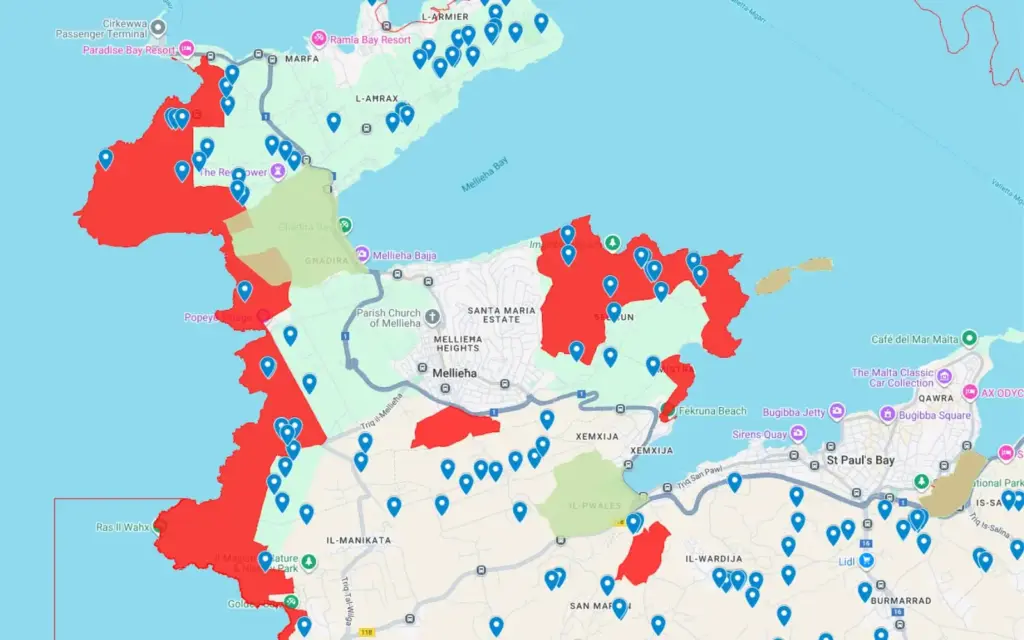

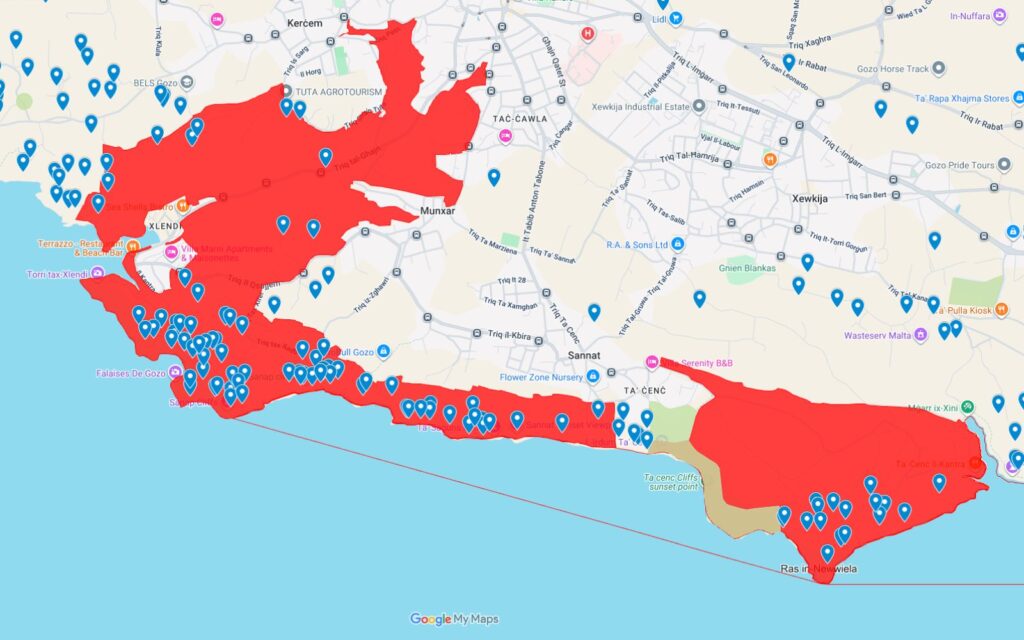

Superimposing the map of 2024’s licensed trapping sites on the map of Natura 2000 sites, which is allowed in Malta, reveals significant overlaps. Trappers can catch birds along the entire protected Southwestern coast of Malta and Southern Gozo. Trapping sites next to bird sanctuaries can also be found. The EU’s court criticised the decision.

Appelgren of MRU reports having observed cases where trappers clear vegetation, drastically reducing biodiversity at the sites they use. “It’s worse than hunting, they kill their land, and so that nothing will grow, and they keep them barren for the purpose of trapping birds,”she said.

In 2014, the FKNK acknowledged the use of agricultural pesticides but claimed this “can easily be reversed”.

Falzon doesn’t see a reason why Natura 2000 protection should exclude trapping. “So you have people fishing, you have people walking dogs and a million other things. Why not trapping?”

Asked about the matter, the European Commission’s spokesperson said that “The Commission has no information on the practice in question.”

Falzon warns that rampant development will likely spell the demise of the trapping hobby. “In the past there were trapping sites all over the place. Now there are far fewer” .

Cauchi of KSU believes that unsustainable agricultural practices threaten finches, and that there is scope for trappers and conservationists coming together to protect birds. “I’d be willing to sit down with another moderate individual, but I cannot sit down with someone whose idea is abolishing hunting and trapping,” he said.

The government’s claims to allow trapping as a scientific derogation are misleading.

The research derogation has resulted in few ring recoveries and, despite hundreds of birds caught and dozens of rings recorded. Trappers’ data has not been cited in published scientific literature that could be found on Google Scholar. Many of the recovered rings belong to birds already caught in Malta. Trappers’ representatives consider that ringer’s refusal to cooperate explains it.

Police presence remains weak, especially in Gozo, while monitoring 4,000 trappers is a major logistical challenge. Many experts, including those in favour of trapping, said the derogation is a guise and that quality data is not being produced. However, KSU expressed willingness to shift its trapper members to ringers in the future.

Rather, as Mark Anthony Falzon puts it:

“[Trapping] is a practice that I think should be absolutely valued for what it is. Malta should make its case that this is a local practice that has value. This is why this deception is going to fail.”

This project is supported by the European Media and Information Fund. The sole responsibility for any content supported by the European Media and Information Fund lies with the authors and it may not necessarily reflect the positions of the EMIF and the Fund Partners, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute.

Leave a Reply