- Malta’s government income comes from two sources: taxes (€6.9 billion) and non-tax revenues (€620 million), like EU grants and administrative fees. Total tax revenues have more than doubled since 2014.

- Income Tax (€2.85 billion), social security contributions (€1.64 billion), and VAT (€1.6 billion) make up the bulk of tax revenues.

- Maltese households provide nearly two-thirds of all income tax collected.

- All government revenues are deposited into the Consolidated Fund, Malta’s central bank account, which receives and distributes funds. Malta’s total income is €7.5 billion.

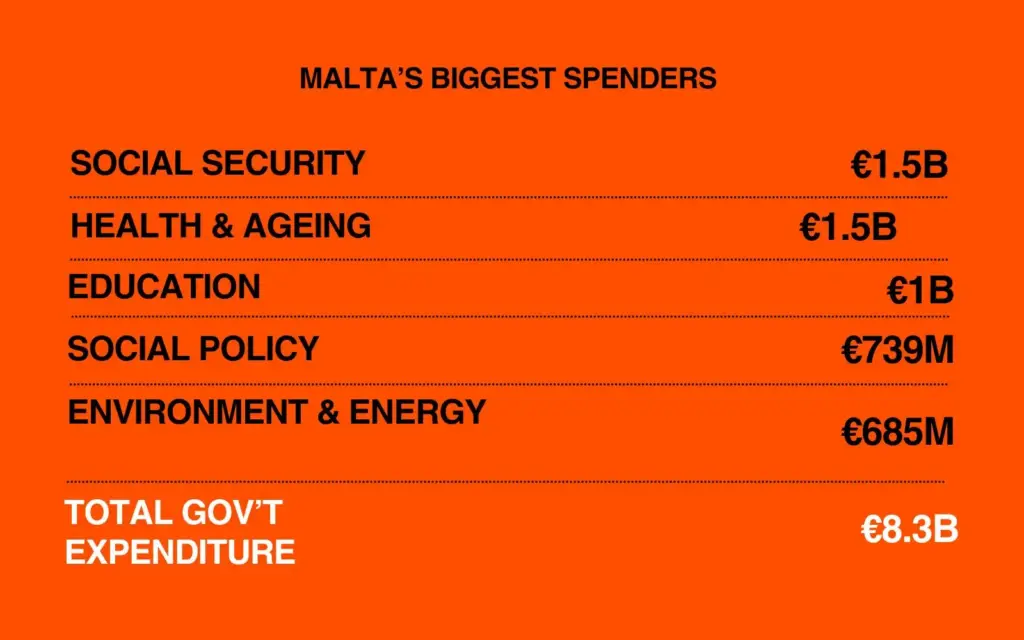

- Malta’s total spending or expenditure is €8.3 billion. This means the Consolidated Fund operates at a deficit, which means it spends more than its income.

- For 2025, budget estimates forecasted €7.3 billion in recurrent costs, or the day-to-day expenses of running a government, and €1 billion in capital investment.

- The largest spending areas are

- Social Security: €1.5 billion or 23% of all spending (Pensions separately cost around €105 million)

- Health: €1.3 billion

- Education: €1 billion

- Social Policy: €739 million

- Environment & Energy: €685 million (which includes the €152 million for energy subsidies)

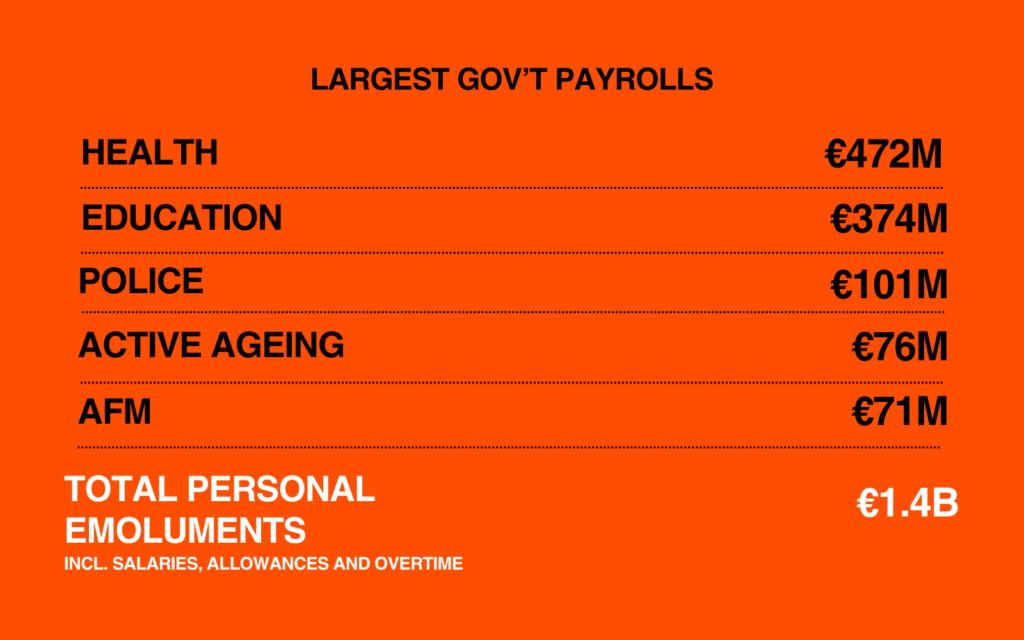

- Salaries, allowances and overtime for all government employees, including MPs and Authority heads, totalled €1.47 billion. The largest payrolls are at the Ministry for Health (472 million), Education (374 million) and the Police (102 million).

- The government earmarked €220 million for third-party contracts and €25 million for consultancy and professional fees.

- The total Consolidated Fund deficit has reduced over the years. However, total government debt continues to increase. Latest figures show it stands at €11 billion, or 46% of GDP, up €1 billion from the previous year.

Each year, the red briefcase appears, the finance minister rises, and the word “budget” dominates the news. Behind the ritual lies a simple question: how exactly does Malta’s government make and spend its money?

The answer involves billions of euros and thousands of line items but one key idea: money comes in through taxes, flows through ministries and programmes, and circles back as salaries, benefits, and infrastructure.

Ahead of the 2026 edition, this guide breaks down the estimates from Malta’s 2025 budget into three parts: where the money comes from, how it’s spent, and how the country manages the gap between the two.

How does the government make its money?

Malta’s government revenue and financing is made up of taxes, non-tax revenues, and borrowing: the three pillars of state financing.

1. Taxes: the backbone of government income

The government’s primary financial engine is its residents and businesses.

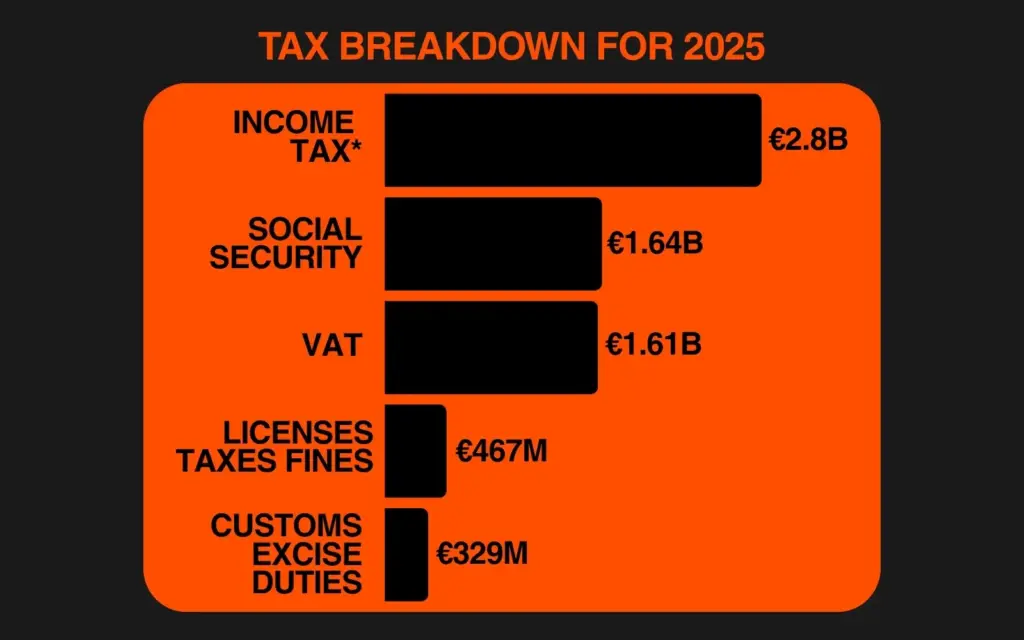

According to the 2025 budget estimates, total tax revenue is estimated at just under €6.9 billion.

Malta’s tax revenues have increased significantly over the last decade or so, coinciding with population and migration growth. In 2013, tax revenues stood at nearly €2.5 billion and reached around €5.6 billion by 2023.

Tax revenues are split into direct and indirect taxes.

Direct taxes, the largest share, are made up of income tax (€2.85 billion) and social security contributions (€1.64 billion). Together, these make up about 65%* of all tax revenues and roughly half of total government revenue.

The latest official data shows that in 2023 alone, households contributed €1.5 billion, or almost two-thirds of all income tax collected. The closest contributors are non-financial corporations (€449 million) and financial corporations (€407 million).

The largest indirect tax is sales tax, or Value Added Tax (VAT), which is estimated to generate around €1.6 billion in 2025.

Here is a breakdown of tax income:

Direct:

- Income Tax: €2,848,000,000

- Social Security: €1,642,000,000

Indirect:

- Customs and Excise Duties: €329,000,000

- Licenses, Taxes and Fines: €467,000,000

- Value Added Tax: €1,611,000,000

Other government income:

Beyond taxes, the government expects to collect around €620 million in non-tax revenues in 2025.

The largest component is grants, mainly EU funding, which support a range of projects, including infrastructure, agriculture, integration, and security initiatives. In 2025, grants are expected to total more than €288 million.

The next biggest slice is “Fees of Office”, forecast at €112.6 million for 2025, which covers a range of administrative income, fees, and charges from government institutions.

Two key contributors here are the Residency Malta Agency (€30 million) and the Granting of Citizenship for Exceptional Services (€30 million). However, this is expected to change following an EU court order ending the citizenship-by-investment programme.

The government also earns dividends from state investments, projected at more than €58 million in 2025, up from €44 million in 2023 but slightly down from 2024’s €61.7 million.

How the Government Spends Its Money

The Consolidated Fund:

All revenue, with limited expectations, including your taxes and social contributions, flows into Malta’s Consolidated Fund.

Think of it as the government’s main bank account, the source of funding for everything from urban greening to hospital maintenance, divided each year among ministries, agencies, and public services through the budget.

The Consolidated Fund operates at a deficit, meaning it spends more than it receives in income. It is expected to stand at almost €744 million in 2025, slightly below 2024’s €771 million.

Recurrent and Capital Expenditure:

In 2025, total recurrent expenditure, the everyday cost of running government and its services, is projected at €7.3 billion . Another €1 billion is earmarked for capital expenditure, long-term investment in infrastructure, schools, and hospitals.

By 2027, total recurrent expenditure is expected to rise to near €8.9 billion.

Government expenditure is grouped into four main categories. Together, they tell you how the €7.3 billion in recurrent spending is distributed.

Programmes and Initiatives dominate the budget, covering subsidies, grants, and social spending, accounting for roughly 60%.

The largest beneficiaries of programmes are:

- Social Security: €1.6 billion

- Social Policy: €544 million

- Health Ministry: €397 million

- Environment and Energy Ministry: €320 million (including €152 million for energy subsidies)

- Finance Ministry: €230 million.

- Active Ageing: €145 million.

- Transport Ministry: €135 million.

- Pensions (for civil servants etc.): €105 million

Out of the €1.6 billion spent on social security benefits:

- €833.8 million is retirement pensions

- €200 million is widows’ pensions

- €147 million is under a bonus

- €90 million is under the children’s allowance

However, this is funded through social security contributions. An additional €105 million is earmarked for pensions.

That means that a total of €1.38 billion is spent on pensions.

Personal Emoluments are salaries, allowances, overtime, and social contributions for civil servants and political officeholders, including MPs and Cabinet members. Around 21% of spending.

The largest payrolls are at the Ministry for Health (€473 million), Education (€375 million) and the Police (€102 million).

Operational and Maintenance Expenses include utilities, rent, repairs, travel, professional services, and administrative costs. These include the €220.8 million for third-party contracts and €25.7 million for consultancy and professional fees.

Contributions to Government Entities, such as state corporations and authorities, absorb the remaining €925 million.

Capital Expenditure:

The government also sets aside ‘Capital Expenditure’ in the budget. Capital Expenditure is public investment in more durable assets, such as infrastructure and major projects.

The largest spenders by capital expenditure are:

| Ministry for the Environment, Energy and Public Cleanliness (includes EU Funds) | €235,115,000 |

| Office of the Prime Minister | €109,437,000 |

| Ministry for Health and Active Ageing | €88,792,000 |

| Ministry for Education, Sport, Youth, Research and Innovation | €88,074,000 |

| Ministry for Agriculture, Fisheries and Animal Rights | €80,776,000 |

Total spend:

The 2025 Budget distributes these billions across Malta’s ministries. The Ministry for Health and Active Ageing takes the lead (€1.5 billion), followed by the Ministry for Education, Sport, Youth, Research and Innovation (€1 billion) and the Ministry for Social Policy and Children’s Rights (€739 million).

Top 5 ministries account for well over half of all government spending:

| Ministry for Health and Active Ageing | €1,528,987,000 |

| Ministry for Education, Sport, Youth, Research and Innovation | €1,032,426,000 |

| Ministry for Social Policy and Children’s Rights | €739,235,000 |

| Ministry for the Environment, Energy and Public Cleanliness | €685,316,550 |

| Ministry for Finance | €449,409,000 |

| Ministry for Home Affairs, Security and Employment | €448,576,000 |

Social security & Pensions: the single largest item

No programme consumes more money than Social Security Benefits, budgeted at €1.6 billion in 2025, roughly one euro in every five spent.

Out of the €1.6 billion spent on social security benefits:

- €833.8 million is retirement pensions

- €200 million is widows’ pensions

- €147 million is under a bonus

- €90 million is under the children’s allowance

However, this is funded through social security contributions. An additional €105 million is earmarked for pensions for civil servants and other public personnel.

The Ministry for Social Policy oversees another €553 million in social spending.

Healthcare follows as the second-largest area of expenditure, with €1.1 billion in allocations for 2025. Within that:

- Within that Active Ageing alone accounts for €305 million. That includes long-term institutional care and community care.

- Hospitals like Mater Dei, Mount Carmel, Gozo General, Karin Grech, and St. Vincent de Paul: €265 million

- Primary healthcare and community services: €73 million

The next is education. The Ministry for Education, Sport, Youth, Research and Innovation receives €485 million, with an extra €459 million earmarked for Education-specific spending. The total budget exceeds €1 billion.

Other major recipients include the Ministry for Environment, Energy and Public Cleanliness at €685 million, which includes the €152 million spent on support measures to keep energy prices stable.

Meanwhile, Malta’s spending on research and innovation as a share of its GDP is the second-lowest in the EU and has decreased since 2013.

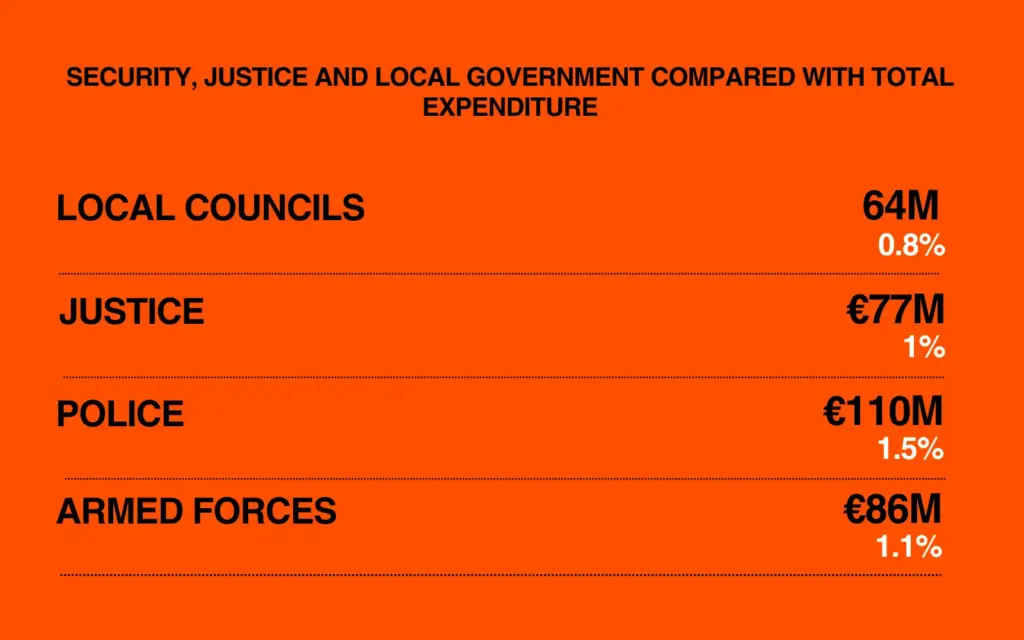

Security, Local Councils and Justice

Despite being fundamental to shaping daily life, security, justice, and local government receive relatively small shares of the overall pie.

The Police were earmarked €110 million for 2025, around 1.5% of total expenditure. However, that is mostly spent on salaries, overtime and allowances, despite relatively little changes in personnel.

The Armed Forces (€86 million or 1.1%) and Civil Protection (€13.9 million or 0.1%) are provided with even less.

Local councils, in particular, operate close to residents and are on the front lines of community issues, but command less than 1% of total expenditure with €64 million earmarked for 2025.

The Ministry for Justice, which also includes the reform of the construction sector beyond its responsibilities over the courts (which have the worst delays in Europe) has a total budget of €77 million, around 1% of total spending.

Deficit and Government debt

Malta’s budget operates at a deficit, meaning the government spends more than it earns. To cover this gap, it borrows money. For 2025, Local Loans, the primary source of covering Malta’s debts, are estimated at €1.5 billion.

Malta’s government has consistently reduced its deficit. The general government deficit declined from 4.7% in 2023 to 3.7% in 2024 and is projected to decrease further to 2.8% in 2026.

Still, public debt servicing, which covers the interest and principal repayments on its outstanding debt, is rising:

2023: €696 million

2024: €787 million

2025: €886.6 million

Projected by 2027: €1.3 billion

According to the budget estimates for 2025, €312 million is allocated for interest public debt payments alone.

By the end of 2024, total government debt was around €10.6 billion, equivalent to 46.2% of GDP. It was up by €821.2 million from the previous year.

As of the end of August 2025, debt stood at €11.1 billion, an increase of €1.1 billion from the same time last year.

Here is a breakdown of spend per Ministry, showing at which sectors the state supports, and which pressures it prioritises:

| Ministry | Estimate | Capital Expenditure |

| Ministry for Health and Active Ageing | 1,528,987,000 | 88,792,000 |

| Ministry for Education, Sport, Youth, Research and Innovation | 1,032,426,000 | 88,074,000 |

| Ministry for Social Policy and Children’s Rights | 739,235,000 | 7,943,000 |

| Ministry for the Environment, Energy and Public Cleanliness | 685,316,550 | 235,115,000 |

| Ministry for Finance | 449,409,000 | 74,621,000 |

| Ministry for Home Affairs, Security and Employment | 448,576,000 | 72,767,000 |

| Ministry for Transport, Infrastructure and Public Works | 328,204,000 | 54,078,000 |

| Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Tourism | 240,384,758 | 10,752,000 |

| Ministry for the National Heritage, the Arts and Local Government | 210,187,000 | 63,210,000 |

| Office of the Prime Minister | 209,175,859 | 109,437,000 |

| Ministry for Agriculture, Fisheries and Animal Rights | 144,378,000 | 80,776,000 |

| Ministry for the Economy, Enterprise and Strategic Projects | 141,257,000 | 77,359,000 |

| Ministry for Gozo and Planning | 93,109,000 | 15,203,000 |

| Ministry for Justice and Reform of the Construction Sector | 77,253,108 | 9,899,000 |

| Ministry for Inclusion and the Voluntary Sector | 63,195,000 | 3,531,000 |

| Ministry for Social and Affordable Accommodation | 55,598,000 | 348,000 |

| Ministry for Lands and the Implementation of the Electoral Programme | 24,700,000 | 10,121,000 |