Malta’s Tax Revenues Rise, But Poor Investment Leaves Citizens And Migrants Struggling Alike

By Daiva Repečkaitė, Julian Bonnici and Sabrina Zammit

Photo credit: Joanna Demarco

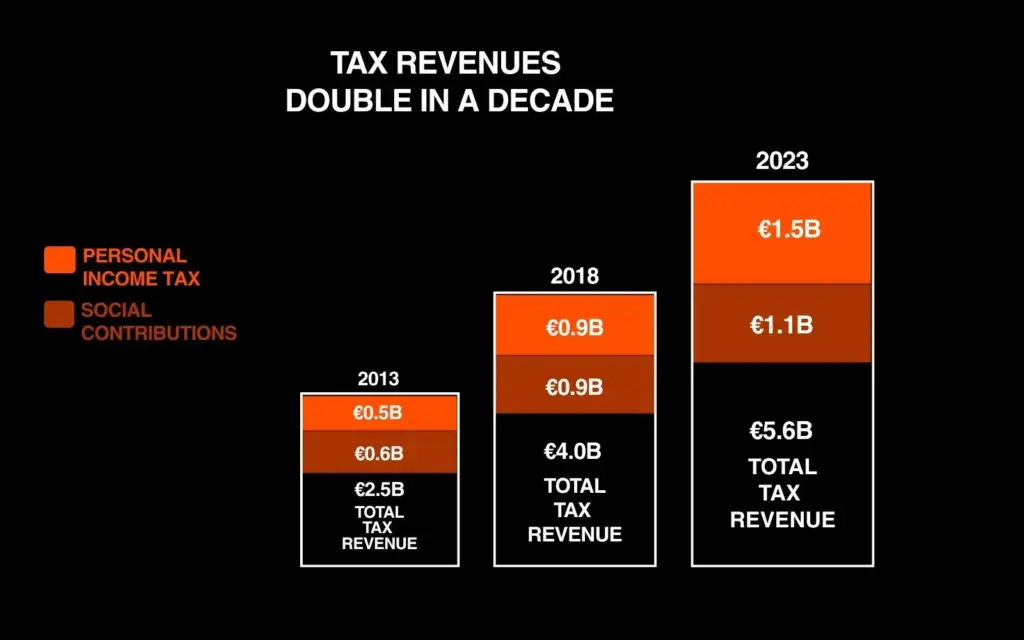

- Tax revenues in Malta more than doubled between 2013 and 2023, rising from €2.5 billion to €5.6 billion, largely due to population and migration growth.

- Personal income tax and social security contributions both nearly doubled over the decade, yet local council funding remains below 0.8% of total tax revenues.

- Despite the population growth, investment in public services has lagged, particularly in healthcare, childcare, and local infrastructure.

- Foreign patients account for over one in eight hospital users, yet legal and administrative barriers persist.

- Childcare services are unevenly distributed, with areas such as St. Paul’s Bay, Sliema, and Marsa underserved, despite having large migrant populations.

- Government funding for after-school programs was reduced by half in 2024.

- NGOs fill widening service gaps by offering healthcare, legal, and integration support, but they face unstable funding and limited government backing.

Taking benefits, using free public services, exploiting tax breaks – a 2023 study shows these are the accusations most often levelled at migrants on social media in Malta.

A cross-border investigation by Amphora Media and our partner Público in Spain reveals that weak government investment in public services – for both citizens and foreigners – fuels tensions over quality and accessibility, rather than migration itself or the tax revenue migrants contribute.

Amphora Media examined key services in localities, many of which border each other, that have experienced significant increases in their foreign population.

Check out all the numbers behind migration and population in Malta over here.

Malta’s Tax Revenues Soar Amid Population Boom

Malta is one of the EU’s fastest-growing economies, with the second-highest employment rate and the lowest unemployment rate in the EU. Still, a 2021 survey showed that nearly half of Maltese respondents viewed migrants as a greater burden than a benefit, and a quarter attributed low wages to migrants.

Malta’s tax revenues have increased significantly over the past decade, coinciding with population growth and migration. Between 2013 and 2023, revenues more than doubled from around €2.5 billion to €5.6 billion.

Between 2013 and 2023, revenue from personal income tax — paid by both Maltese and foreign residents — increased by nearly €1 billion, a rise of approximately 190%.

In 2023 alone, households contributed €1.5 billion, or almost two-thirds of all income tax collected.

Employee social security contributions, which cover pensions and other benefits, also more than doubled, climbing from €200 million in 2013 to more than €447 million in 2023.

Average monthly salaries rose from about €1,335 in 2013 to €2,125 in 2025.

Yet, investment in local councils, which are often on the front lines of population transformation and the tensions that come with it, remains limited.

The 2024 budget for local councils was slightly above €48 million across 68 localities. That’s around 0.8% of the total tax revenues generated.

Healthcare: who pays?

A survey found that most Maltese people see a high concentration of immigrants as an obstacle to integration. Yet only a third, the lowest share in the EU, viewed limited access to healthcare, education, and social services in the same way.

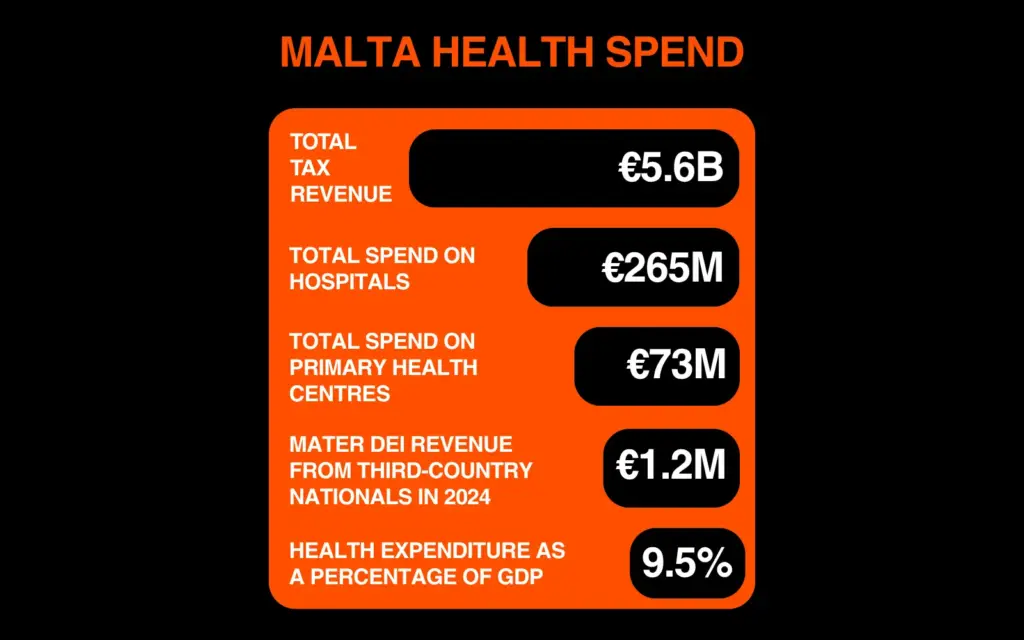

Approximately €73 million is allocated for primary health care and community services. At the same time, hospitals such as Mater Dei, Mount Carmel, Gozo General, Karin Grech, and St. Vincent de Paul collectively receive €265 million.

Combined, this represents roughly a quarter of the Health Ministry’s budget and 6% of total tax revenues.

Data shows that the number of Maltese citizens visiting Mater Dei has grown, and visits to health centres have fluctuated since 2020.

Malta has one of the highest out-of-pocket spending rates in the EU. In 2024, Researchers say that despite this, the share of unmet needs is low.

This includes the migrant population. An EU dashboard shows that Maltese citizens are more likely to consider their health bad or report a long-standing illness.

The latest Migrant Integration Policy Index states that “healthcare entitlements remain discretionary, and documentation and administrative barriers continue to pose challenges”, making the system “halfway favourable” to migrants.

According to a 2024 report by the European Observatory for Health Systems and Policies, Malta has fewer acute care beds and less specialised equipment than several other Mediterranean countries and fewer than in 2022. At the beginning of 2023, the pain clinic had a waiting list of over 200 people.

Foreign residents constituted more than one in eight patients at the main hospital in 2023 and one in six users of the health centre.

Their number has more than doubled since 2020, but is still below the share of the foreign population in Malta, which was 29% in 2024. A report warns that mental healthcare for migrant and refugee populations is “a major concern”.

Legal changes introduced in 2024 require many non-EU nationals applying for employment, family reunification, or studying outside recognised public institutions to obtain private health insurance with at least €100,000 coverage. However, students at Malta’s public universities and institutes are exempt from this requirement.

Between 2022 and 2023, hospital revenues from paid fees increased by more than 100%. In 2024, the hospital received €1,323,284.36 from third-country nationals.

“What we find with healthcare, and particularly in the last couple of years, is that things have really kind of stepped up in terms of payments, cracking down on making sure that people are charged and people’s documents are checked very thoroughly,” says Beth Cachia, research and advocacy coordinator at Jesuit Refugee Service, which helps refugees and asylum seekers navigate bureaucracy.

In 2024, the NGO helped 53 individuals with healthcare needs. Cachia warns of “ instances of people, even with a refugee status, turned away” despite healthcare falling under the protection of asylum seekers.

Umayma Elamin Amer Elamin, the founder and president of Migrant Women Association Malta, detailed how migrant women face similar challenges:

“Sometimes they get all the medicine, sometimes she will need to buy it herself. Sometimes, if they have an operation or an illness, they may need to wait. When it comes to communication, I feel translation is also a big issue,” she said, making particular reference to STD screening.

Gaps in Primary Care

Although the government claims that primary health centres are strategically located, St Paul’s Bay, with a total population of 35,000 (almost 60% foreign), does not have one.

Neither do Sliema and St Julian’s, which, with a combined population of more than 34,000, must use Gżira’s. Marsa (part of the Southern Harbour, where most migrants are non-European) also lacks a healthcare centre.

2024 data shows that Mosta Healthcare Centre, which has a large catchment area, handled the largest number of emergency visits.

Paola, which had the second-highest number of emergency visits and covers several southern localities, including Marsaskala and Birżebbuġa, topped the list by the total number of patients.

Caring for the youngest

Free childcare is provided to working or studying parents not on parental leave. Foreigners working in Malta are eligible too.

The distribution of these vital facilities did not mirror the population:

- In Gozo, only Victoria had childcare centres available from the localities included in this analysis.

- In the South, Birzebbuga had two childcare centres and Marsaskala had four.

- The much less populous Pieta’ and Gżira had five and six, respectively.

- The populous St Paul’s Bay only had two.

- In Sliema, where the majority of pupils at schools are foreign, there are only two childcare centres for younger children.

- St Julian’s is a smaller locality than Sliema, but there are three childcare centres.

Parents in full-time employment can place their children in after-school centres. The government considers that the introduction of free childcare, including for school-aged children, is behind Malta’s success in raising female employment rates.

As of early 2024, the 3–16 centres in Sliema and St Paul’s Bay had waiting lists of 25 and 28 children, respectively.

According to the 2024 financial estimates, the government reduced funding for after-school clubs by almost half, from €9 million to an estimated €4.8 million, between 2023 and 2024.

For migrant mothers without established family networks, access to childcare can significantly impact their employment prospects.

“I can confirm this is the big challenge for a woman, to have access to the labour market and to get enough funds to live easily in Malta. I can see the majority of our beneficiaries have this problem,” says Elamin. “Sometimes they can’t work, for example, because of their situation or maybe because they are married and they have children, or they don’t have access to services that can help them to work with their children.”

The Expats Malta Facebook community also guides its members who seek better schooling for their children.

“If you’re a typical family, it’s fine, no problem. You move to a village, you’re in the catchment area for a school, and that’s where your child goes. But if you come as a single parent, they’ll ask: do you have a letter of authorisation from the other parent? Even if you have full custody. It’s all these small things where the right information is just missing,” one of its administrators, Tom Erik Skjønsberg, says.

NGOs stepping up without public investment

NGOs, such as the Migrant Women Association Malta, and communities attempt to fill the gaps left by state authorities. The association has begun incorporating social services into its training and entrepreneurship portfolio.

“We have become like one of the organisations that have a social service directly to the asylum seeker, refugee, and migrant woman. But specifically those affected by poverty and sexual gender based violence,” says its founder, Umayma Elamin Amer Elamin.

Since last year, JRS Malta, where Beth Cachia works, is partnering with aditus Foundation and Migrant Women Association Malta to jointly provide legal, psychological and social work services, cultural mediation, and basic integration support services to vulnerable individuals.

However, without sustained funding, it can be difficult to maintain.

“We had something before. We used to study Maltese, English and some arts as well. Computers too. But because of COVID-19, we closed and we didn’t open it again,” Mohamed Ibrahim from the Sudanese community told Amphora Media.

“Unfortunately, we didn’t [find government support]. We used to collect money to pay the rent and we had to close it. We didn’t even try find a place for us because the support there once was lost.”

This investigation was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.