Currently viewing:migration

-

The Numbers Behind Malta’s Labour Migration Model

-

EU’s New Safe Countries List: Why It Changes Little For Malta And Deportations

-

FATTI: Is Malta’s Native Population At Risk Of Collapse – And Can Tax Cuts Stop It?

-

Landscape of Change:The Numbers Behind Population And Migration In Malta’s Towns

-

Malta’s Tax Revenues Rise, But Poor Investment Leaves Citizens And Migrants Struggling Alike

-

Local councils: Underfunded, Burdened By Waste, Committed To Guiding People Amid Population Growth

-

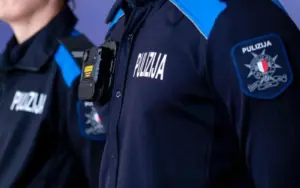

More People, Same Police, Bigger Budget: Malta’s Enforcement Struggles To Keep Pace With Migration

-

Landscapes Of Change: Malta’s Integration Strategy Fails To Match Migration And Population Growth

-

FATTI: Is Malta “full-up”?

-

Logged Pushbacks to Libya from Malta’s SAR Zone Triple Since 2020, Over 5,000 People Forced Back