Landscapes Of Change: Malta’s Integration Strategy Fails To Match Migration And Population Growth

By Daiva Repečkaitė, Julian Bonnici and Sabrina Zammit

Photo credit: Joanna Demarco

Over time, the image of migrants has changed in Malta, from minorities in need of help to workers who “have supported the economy on multiple fronts”, shored up the pensions system and filled skills gaps

Yet, Amphora Media’s review of national policies and EU-funded projects indicates that migrants have more often been seen as a problem to manage rather than fellow residents.

Only one local council in Malta and Gozo, Sliema, has managed to follow through with an EU-funded project related to migrant integration.

Positive attitudes towards the Integration of migrants appeared to be gaining ground by 2021 compared to 2017. One in three Maltese respondents said that the government should consider integration of non-EU migration as its top priority, roughly half said it should be prioritised more.

“Integration pathways have the potential to contribute to further wealth creation while fostering safe communities for everyone,” Parliamentary Secretary Rebecca Buttigieg proclaimed in the current Integration Strategy and Action Plan 2025-2030.

But with tensions continuing to rise and politicians warning of Malta’s declining birthrate, have strategies and reforms actually brought about change?

Asylum seekers placed in struggling communities

In 2005, the government opened the Marsa Open Centre for asylum seekers. By the time the government closed it in 2024, the total number of asylum seekers housed in facilities of this type was under 200.

According to the latest data, Marsa’s population is around 5,600, and over a quarter of its residents are foreign. In 2011, the foreign population was 147; by 2022, it had increased to 1,561.

“The introduction of an open centre [predominantly] for sub-Saharan African migrant men in 2005 saw a sudden shift in the demographic population of Marsa, as hundreds of socially marginalized men were relocated within a dilapidated trade school on the outskirts of the town, whilst others sought to take advantage of cheap rent in the area,” Sharon Attard wrote in her PhD dissertation.

Back then, the locality was also “ageing” and “segregated”, according to the Kopin NGO. Based on her fieldwork in Marsa for her PhD, Attard concluded that after the open centre opened its native-born residents felt “forgotten”.

Marsa also housed a heavy-fuel oil power station built in the 1950s, until 2014. It was among 622 facilities in the EU that contributed the most to the costs of environmental damage.

According to the Housing Authority, the average price for a two-bedroom apartment in the area is €600, well below the €1,200 price in areas like Sliema and St Julian’s, which host more affluent migrants.

When Kopin, a human rights NGO, interviewed African residents of Marsa about their experience in 2017, the interviewees mentioned racial profiling and unfair treatment by the police. Yet they added that the availability of affordable housing and jobs kept them in the locality, where some of them eventually opened their own shops.

Issues do remain in the area. Recently, the government launched an urban regeneration project for Marsa. As of 2024, Marsa has a comparatively high council budget per capita, with almost €686,700. But when accounting for inflation, it has increased by less than a quarter since 2013.

For a time, the Sudanese community had premises in Hamrun, which is within walking distance from Marsa, for various upskilling and community-building activities. The centre even ended up in the official programme of the Valletta European Capital of Culture events.

“We used to study Maltese, English and some arts as well, computer [literacy too],” says Sudanese community leader Mohamed Ibrahim. He explained that it was difficult to pay rent for the premises. After losing the physical space to gather, the community is not that active, even though Sudanese asylum seekers continue coming to Malta.

Workers in focus

According to researchers behind a 2023 study, when Maltese residents considered themselves victims of population developments, they blamed asylum seekers arriving by boat for this. But migrants in Malta are not limited to asylum seekers. Malta’s booming economy has attracted people from all over the world to work.

A 2005 document focusing on irregular migrants highlights the differences in policy challenges compared to today.

Irregular migration posed “challenges to the labour market”, it said. However, Malta already had a low unemployment rate, compared to other EU countries, and only 3.2% of residents were foreign citizens at the time.

According to the Central Bank, between 2007 and 2018, there were more EU than non-EU workers registered in Malta, fuelled by economic crises, particularly from countries such as Italy, the UK, and Bulgaria.

In 2017, the government simplified the procedures for employing non-EU workers, and by 2018, the net immigration of non-EU nationals outnumbered EU nationals.

In an interview with The Malta Independent in 2018, Clyde Caruana, then chairman of JobsPlus, stated that JobsPlus was pursuing the employment of third-country nationals to sustain Malta’s economic growth and its pension system.

“If the economy continues to grow we will have to import foreigners no questions asked. If we don’t, the economy will grow at a smaller rate,” he said.

By 2021, the Malta Chamber of Commerce, Enterprise and Industry called on the government to reform taxation in a way that “attracts not detracts foreigners from working in Malta” and to launch “an international marketing campaign showcasing Malta as a career destination”.

Today, the issue identified in policy is high turnover of foreign workers, and one of the strategic objectives is “better working conditions, matching of skills and upskilling”. The National Employment Policy 2021-2030 acknowledged that “the inflow of migrant workers played a key contributing force to Malta’s buoyant labour market.”

Workers in the gambling sector (so-called iGaming) are a special case. According to the Malta Gaming Authority, close to 9,900 foreigners were working in the online gambling sector.

They are not mentioned in the migrant integration strategy, but the Labour Migration Strategy promotes exemptions for the gambling sector from seeking to employ a Maltese/EU/EEA national first before offering a job to a non-EU national, and from limiting the maximum number of non-EU nationals upon recommendation of Gaming Malta.

It is difficult to find precise data on the integration of gambling sector employees, but, according to the Gambling Insider magazine, Sliema, Msida, Gzira and St. Julians are “well known for housing international (and local) iGaming workers”, and these settlement patterns have reshaped Malta’s housing landscape.

The localities also face signficant over tourism.

Malta, its Government and the attempts at Integration Policy

The Labour Party came to power in 2013, and the same month, the Ministry for Social Dialogue, Consumer Affairs and Civil Liberties was set up, tasked, among other duties, with migrant integration.

By the end of 2015, it had announced an integration project, hosted a conference on integration, set up an integration portal with the International Organization for Migration and launched a public consultation on integration.

A 2016 archived copy of the government’s integration website shows attempts to set up a portal of advice and information for foreigners in Malta, with sections on education, health and ‘social issues’. Among other things, it promised free childcare to non-EU nationals’ children, as long as the parents work or study in Malta.

At the time, under 13% of Malta’s population was foreign, nearly equally shared between EU and non-EU nationals. This balance shifted in favour of non-EU nationals in 2018.

In 2017, a new strategy document promising a “stronger framework for integration” was introduced. In it, then-Minister Helena Dalli wrote, “For Government, it is important that no individual or community feels isolated from those around them.”

The document promised that “A migrant integration perspective should be incorporated in all sectors, such as education, employment, health, social services and other sectors, and at all levels and stages”. It launched the I Belong programme, where any migrant, from the EU or not, would submit a request, receive guidance by cultural mediators and an app, and attend language and cultural orientation classes.

Mohamed Ibrahim, a Sudanese community leader who spoke to Amphora, praised the programme’s interesting content and good teachers, but admitted it was not easy to convince others to sign up for the course.

Kirstin Sonne, who has published an academic study on the programme, told Amphora Media that the way the programme is designed encourages a specific kind of migrants – those who have already made headway in Maltese society. “

A couple of people said that it would be more helpful if they had done it much earlier. After living in Malta for five years, you don’t really need to be told about the festa. You’ve seen it many, many times. So, there was a sense that this would be good when you first arrive,” she said.

She is critical of using the programme as a requirement for migrants to access rights.

“The whole concept of integration is, I think, problematic. What is the Maltese society? Is it really a homogeneous thing that you can integrate into? If there aren’t infrastructures and policies in place to accommodate a diverse population, then you are going to have migration problems,” she said.

Evaluators of the programme noted that their milestones were ‘vague’ and there was no evidence that evaluation was conducted.

According to African Media Association Malta, despite their vital role in the integration process, “NGOs in Malta face significant challenges in their efforts to support migrants. Funding is available, but the administrative red tape can be daunting”, also, “inefficiencies and duplication of services” emerge when the government and NGOs carry out similar actions.

Where did the funding go?

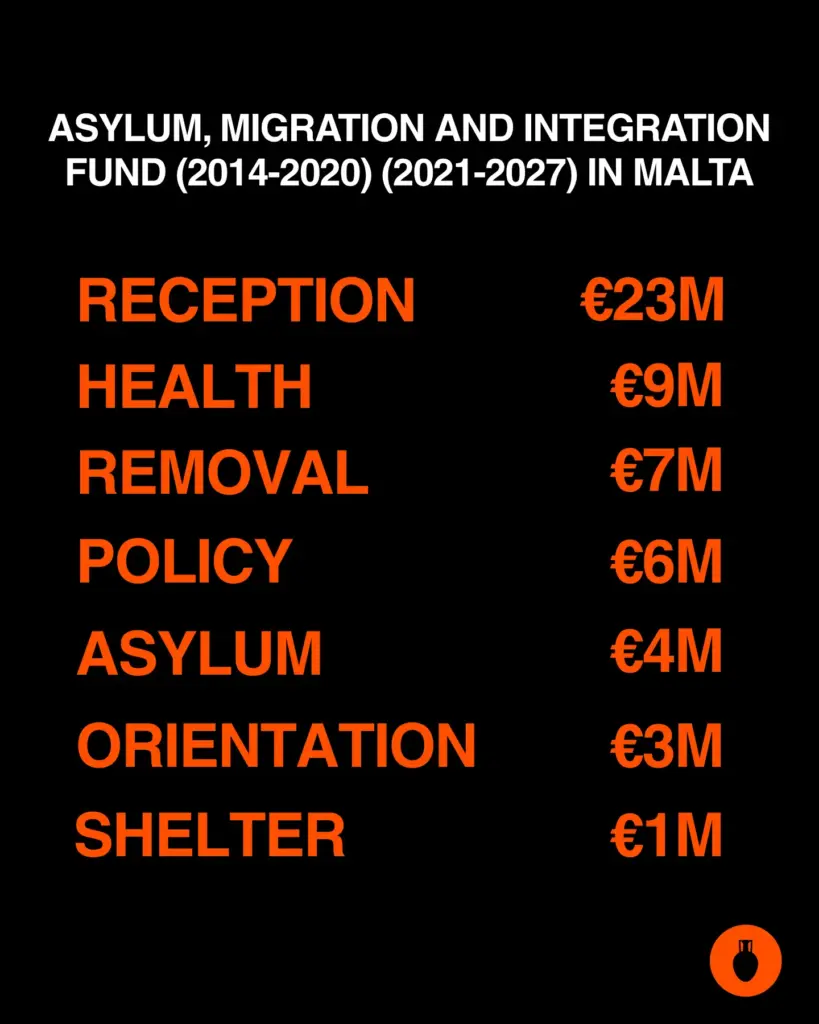

Malta has benefited from EU funding for migration-related policies under different funding instruments: the European Integration Fund, the European Refugee Fund,and later the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF).

These funds were open to government entities, NGOs, local councils and others. During the 2014-2020 period, when AMIF funds were disbursed, 24 projects received €21.7 million from the EU – of these more than €20.2 million went to the central government and only €1.4 million to everyone else.

The AMIF was used, for example, to isolate asylum seekers with infectious diseases (nearly €467,000) and build walls at an open centre (over €102,600). Implementation of the government’s integration strategy, including the I Belong programme, received €1.4 million from the EU – more than all NGOs combined.

By examining the treatment of migrants that received EU funding, it is clear that the bulk of EU funds went towards improving reception conditions for asylum seekers, followed by education initiatives (including I Belong) and healthcare. Removal of migrants from Malta by return or relocation was also quite prominent.

During the 2021–2027 period, the bulk of AMIF funding in Malta was directed to government-managed programmes. Of the €33 million allocated across 12 projects, the majority went to government entities, with only a small share reaching NGOs and other organisations.

Most funding supported reception of asylum seekers, followed by policy support—including implementation of the government’s integration strategy—and health services, while migrant return and removal operations also remained significant.

All this time the only local council to receive support from these funds was that of Sliema, during the 2013-2020 period.

Over the decades, Maltese authorities published three evaluations on EU-funded border, asylum and migration measures.

Two of these documents are a summary of projects in different countries and do not mention migrants at all. The third one was done before the activities were completed and acknowledged that it was too early to say whether it added value.

Relevant government entities do not publish evaluation reports on their policies online, making it difficult for outsiders to analyse what has been achieved, if anything, during the years of integration policy.

As for the European Social Fund, all published evaluations were ex ante, meaning they were conducted before the programmes began.

We sent questions to various responsible ministries and the Parliamentary Secretary for Equality and Reforms. They did not reply.

Beth Cachia, who works at the Jesuit Refugee Service, believes that integration policy should not rest on a series of EU-funded projects. “An integration strategy should be a structural thing that the government produces, not as part of an EU-funded project,” she told Amphora Media.

This investigation was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.